The Tesco fall from grace was well documented in South Africa as the then UK CEO Richard Brasher left the group in 2012. And it wasn’t a year later that he joined Pick n Pay as CEO, to help turnaround the ailing retailer. While the British supermarket giant reported a 2 percent drop in sales for the first quarter of this year, following the group’s record annual loss last year, the picture is a little rosier in South Africa. Pick n Pay’s latest results, the second under Brasher, exceeded expectations. Overhauling its structure to focus on a more centralised distribution network, helped reduce costs and ease the pressure of muted consumer spending has paid dividends. In this article Ted Black looks at what Tesco is implementing to help earnings going forward, something South African retailers may look at down the line. – Stuart Lowman

By Ted Black

We can learn much from Tesco. It posted a huge loss last year – one of the biggest ever recorded in the UK. Yet, fifteen years ago, early in Sir Terry Leahy’s term as CEO, the firm was an exemplar for the “Lean Management” movement which arose out of Toyota’s production system.

Leahy and his team designed the business to meet the “Lean Goal” – a constant search for ways to reduce the time it takes from paying to being paid. Why? Because it means you have to run your business superbly. You have great relationships with suppliers and customers. Your people have clear tasks and know what and how they contribute. Your stock “spins” through the system in a smooth flow.

For most food retailers the cash-to-cash cycle is a negative one. They don’t “turn” their inventory. They “spin” it. They sell and get paid for it several times over before paying suppliers. Watching a US supermarket stocking its shelves is how Taiichi Ohno, the designer of Toyota’s production system saw inventory as “waste” – the root of all evil for a business.

Fundamentally, the value-of-a-firm (VOF) derives from the productivity operating managers generate from the assets they “own” and manage. The best way to measure their ability at doing it is with Cash ROAM.

It asks you two marketing questions:

- For every Rand of Assets, how many Rands of Sales are we generating?

- For every Rand of Sales, how many cents profit do we make?

Multiply the two and you get the ROAM number. Looking at Tesco, the profit number is before interest and cash but after adjusting for working capital. In other words, profit is based on “Sales-in-cash banked” and cash paid to suppliers.

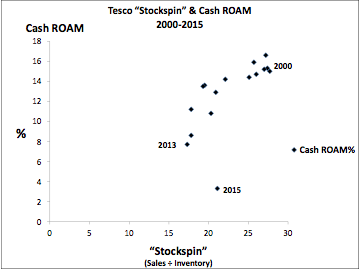

Here is the effect of “Stockspin” (Sales ÷ Inventory) on Tesco’s Cash ROAM since 2000.

The correlation is clear. As “Stockspin” rises from left to right, so does the ROAM. From 2000 to 2002 Leahy’s team spun their entire stock never less than an astonishing 27 times a year reaching a Cash ROAM of 16.6%. Then the fall began. It reached the lowest level of stock productivity in 2013 at 17.3 – still high by most standards but a 38% drop.

This has been the effect of falling ROAM on the value of the firm (VOF) calculated as a ratio – Market Cap divided by total assets.

Again, a clear correlation. As Cash ROAM rises from left to right, so does the value of the firm. With Tesco, the sales productivity of the total asset base also fell – from 2.1 to 1.3 – a drop of 40%.

So what happened? Reading the annual reports is laborious. In 2002 it was 40 pages long. By 2011 it reached 160 pages with 42 of them devoted to corporate risk and governance. That gives us a clue.

Management developed slogans, Jack Welch’s hype of being “Number 1 or 2”, and a steering wheel based on the balanced scorecard with myriad KPAs and KPIs – the bureaucrats’ dream. Their dead hands coupled to the urge to diversify effort and “risk” led them to losing their way. A lack of ethics, despite all the pages of good intent in the annual reports, added to the problem. Hence the big “write-offs” of stock and property values last year.

The reality is that the world is not balanced which is why “balanced scorecards” are “oxymoronic”. If you want change, you can’t get it with many numbers. You do it with one critical number. As Peter Drucker said many years ago, “Concentration and focus is the key to economic results”.

In Tesco’s case it’s clear which measure is the one that matters most not so? “Stockspin”

The new CEO knows that. He is focusing on product range and cash flow. He has to because he and the other big retailers in the UK face tough competition. The big four retailers carry around 35,000 products. ALDI, the German discount store carries 1,350. That’s 3.9% of Tesco’s range.

ALDI “makes it easy” for customers to do business with them – the marketing task – and grew more than 30% in 2014. Most marketing people don’t make it easy.

Myopically, they ignore the sales productivity of assets, and focus on sales in isolation, and “margins”. Give them free rein and they’ll build warehouses and outlets filling them up in an instant with huge variety and countless options. This makes it difficult for customers to choose and slows down stockspin. Simplicity wins every time.

What experience does Pick n Pay… and maybe a few others in South Africa… share in common with Tesco do you think?