Occasionally we get the opportunity to focus on something that really matters rather than feeding our community’s voracious appetite for the drama that news delivers. Gender equality really does matter. From a purely rational observer’s perspective, a patriarchal society is guaranteed to underperform economically because half the workforce is being disadvantaged. For another, it illustrates whether a nation’s aspirations are properly aligned. Whatever other mis-steps, since 1994 South Africa’s promotion of a non-sexist society has delivered considerable progress – it edged up two more positions to an impressive 15th of 144 countries in the WEF’s annual gender equality list, one of the few global league tables where it is moving in the right direction. Analysing the list also emphasises SA’s cultural misalignment with its BRICS partners, all of whom are far down the table and none showing much interest in tackling their serious gender inequality. I spoke to one of the authors of the report, the WEF’s Till Leopold, who laid bare the fact that even though women globally are just as well educated and work longer hours than men, they only earn half as much. And the fairer sex is also most at risk by the dawning of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. – Alec Hogg

Joining us now from Geneva is Till Leopold, from the World Economic Forum. Well, Till, the numbers are out for the WEF’s Global Gender Gap Report for this year. Unfortunately, though, there’s been what you call a dramatic slowdown. Is this reflecting a tougher global economy?

Good afternoon from Geneva, Alec. Yes, so as you just mentioned, this is the 11th year that we’re doing our Global Gender Gap Report. We are finding that the progress on gender parity has dramatically slowed this year. This is largely due to a slowdown in the economic sphere. Despite continuing progress across education as well as the political sphere; unfortunately, we are seeing this slowdown in the economic sphere this year. After a high point in 2013, we have actually reversed all the progress that has been made since 2008 and we’re now projecting that the Global Gender Gap and the economic sphere will not be closed for another 117 years.

2008: that means everything you’ve made in the last eight years (or that the world did in the last eight years) to close this gap between males and females, has been reversed. That’s quite dramatic.

That is what we are finding. An important caveat to mention with our methodology is that this projection that we make for how many years it will take to close the gap, is not a foregone conclusion. That is not fate. That is seeing the rate of progress of the world this year that we’re seeing if things continue – business as usual. That is the progress we’re looking at. Of course – very much -, the message of this report and the point we want to make to the world is that countries do have a chance to influence this and to accelerate the progress as well. For this year unfortunately, we are seeing this slowdown and indeed, this reversal.

Just go back a little bit. How can you have a regression that wipes out the gains of the last eight years? There must have been some influencing factors.

Firstly, we are seeing uneven progress around the world so to a large extent, some of the stalling is coming from countries that have previously made a lot of progress and where the rate of progress has now slowed down. In particular, a lot of the richer countries in North America as well as the European Union have really slowed down in the economic sphere. We are still seeing continuing progress across some of the emerging worlds. Africa is actually doing relatively well, so we’re projecting 63 years to close the economic gender gap in Africa, for example and in Latin America as well, we are seeing some progress. There are a couple of reasons. There isn’t one explanation that explains everything for the slowdown. Some of it clearly has to do with the aftereffects of the global economic crisis from 20058/2009, which are only now playing out to the extent that job creation in general has slowed down.

The economic environment is tougher and that also of course, even with regard to closing the gender gap and just the environment, is much less favourable to making any sort of progress on any front (and therefore, in the economic sphere). That explains part of that but a bigger and more long-term reason that we’re also observing a lot of progress in the education sphere and women’s educational attainment has now actually caught up. The gender gap in education has been closed in many countries but that progress in education doesn’t necessarily translate into an uptake in higher workforce participation of women, particularly in more skilled jobs. One way of looking at our finding is indeed, that it was perhaps easier to make progress from a lower base in the past (due to catching up on education, etcetera).

Now we are really moving into a level where any further progress will require some structural change such as better care policies and better policies around parental leave to really enable countries to take advantage of all this progress that has been made in education as well as in the economic sphere. Of course, that change will not be as quick as some of the progress that has been made in the past.

The reality when you look at these numbers, is that women are working harder than men. They’re going to university even more than men and they’re only getting paid half of what men are being paid and so, it appears as though we live in a very patriarchal world and one where breaking down those barriers is becoming increasingly difficult.

Yes. For example, in South Africa women work, on average, 48 minutes more per day than men do and more than half of their work is still unpaid. That is a trend that is playing out in a similar way across the world so pretty much everywhere, if you combine paid and unpaid work women are working longer hours than men but the burden sharing of unpaid work in the household etcetera, is still predominantly on women. A more equitable distribution of unpaid and paid work would definitely be a big part of the solution here.

It was very interesting that the World Economic Forum has taken up the cudgels on this side. Yesterday, South African Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka who is the Head of Women for the United Nations, gave a speech in the UN General Assembly and she said some interesting things. I’m going to bounce these off you and get your views on it, given that you’re one of the authors of this Report. She said that in Mali, where they have a peacekeeping force: of the six peacekeeping groups…of the 62 members, one is a woman. In the Central African Republic of all Members of Parliament, only eight percent are female. Then she went on to Afghanistan where only two percent of the police force are female. It almost seems as though where things are going well (like in the Nordic countries), it’s brilliant but where things are not going well (like in those countries that are mentioned and others that you bring out in your report, such as in South Asia) it’s horrific, where women just don’t even get a shout or an opportunity. How much of this is history? How much of this is cultural, and how much of this is changeable?

One thing to bear in mind here is that progress in one sphere accelerates progress in the others as well. We’ve already spoken a little bit about education so obviously, that is also a precondition to women getting more quality employment in the economic sphere. In a similar way, in our analysis we find that clearly, broader political empowerment for women, a bigger woman’s share in Parliament for women at the Government’s level is quite strongly correlated as well, with economic progress. Clearly, there is probably a kind of a tipping point where once you have a better gender balance in public administration and the political sphere, that will lead to better policies – not just for women. A number of studies (even beyond our report) have found that it’s actually the diversity and the balance/parity that actually matter so this is not about women as such, but really about the balance.

Therefore, it is probably easier if you’ve made a lot of progress in one sphere, to also leverage that progress to accelerate progress in another level/sphere. However, in some of the countries you mentioned, we are seeing progress (even at a quite symbolic level). For example, some of the countries you mentioned earlier, such as the Central African Republic or even Pakistan, have had a female Head of State – something that a lot of countries in Europe, for example, have not yet had. There are complex factors at play here and I think what is important is that we shouldn’t wait to make progress in one sphere to make progress in another, but rather that it all feeds and promotes each other in this virtual cycle.

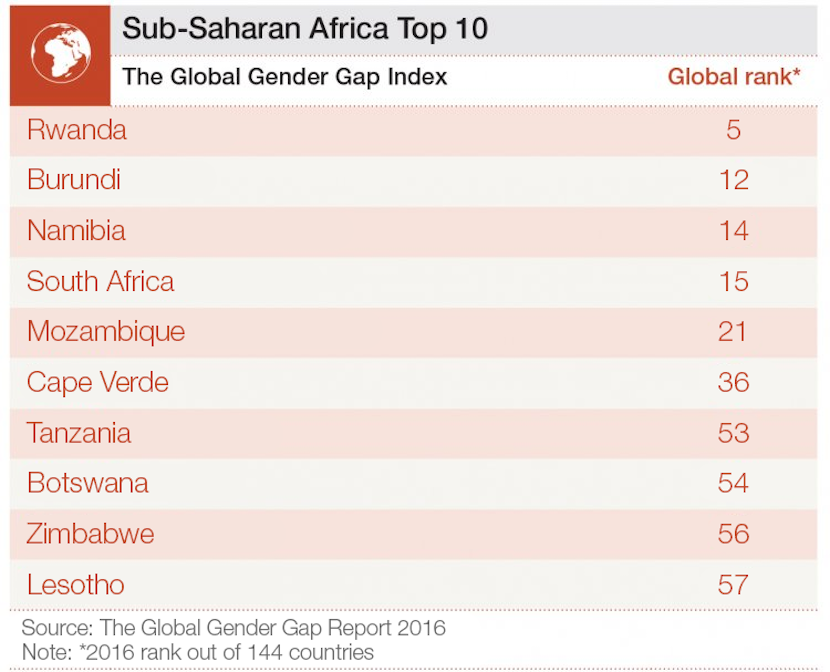

The headline though, is that females have only 59% of the advantages of what males have now, which is the same as they had back in 2008. That was the big headline coming out. The second thing as far as a country like South Africa is concerned: it performs extremely well in this regard – number 15 in the world out of 144 countries that have been analysed. However, the other members of BRICS are really doing poorly. Russia’s at 75th. Brazil is 79th. India is 87th. China is 99th. I guess there would be pressure perhaps, on those members of BRICS to be pulled a little more into the real world by the South African example.

Yes, indeed. South Africa is leading the BRICS group by quite a big margin, as you’ve just mentioned. It also has improved against itself this year so South Africa has been rising two ranks from last year’s report and making continuous progress in the economic sphere, as well as in the political sphere. South Africa has closed 76% of its gender gap, compared to 68% for the world that you just mentioned. Incidentally, for the broader Sub-Saharan African region, the progress is also 68% so Africa is on the world average on those trends. For the other BRICS countries…every country has a different situation to look at. For example, India has also made a lot of progress this year. China’s progress has stalled this year and of course, each of those countries also does have quite a different starting point/history/culture but certainly, within the BRICS group South Africa is clearly the strongest performer and has been for a number of years.

South Africa report

Your boss, Professor Klaus Schwab who clearly was instrumental in bringing this survey to life 11 years ago has highlighted the concern that he has about further regression in the gender equality because of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. How big a threat is this? If we’ve already seen the economic issues (or tougher economic conditions) affecting the progress in gender equality, will the Fourth Industrial Revolution make it even worse?

Thank you for mentioning this forward-looking perspective. Indeed, the Fourth Industrial Revolution is a notion that hit the forum this year and Professor has been emphasising it. We certainly do believe that a lot of this technological progress that is happening simultaneously in fields such as the industrial internet, bioengineering, robotics, and artificial intelligence: all these things will lead to quite dramatic disruptions and changes in the labour market and that is certainly something that you’re already beginning to see, such as the online platform economy and so on. We actually put out a report earlier this year, which looked at the implications specifically of that for gender equality.

What we found is that indeed, some of the job families, which are projected to grow in this environment such as e.g. computer science, engineering, and mathematics etcetera are obviously fields that have – in many countries – historically had relatively few women participating in them. Certainly, in many labour markets and many countries around the world. Some of the job families that have been (even historically) provided with a entry point for women into the labour market such as office roles and general white collar employment are some of those job families that a lot of experts are expecting to be affected by things such as machine learning and increasing automation. On current trends: yes, there is a concern that this Fourth Industrial Revolution could again reverse progress that has been made on women’s economic participation and that would be really bad.

Also, not just for the women seeking good quality jobs in the economy themselves but also, the companies are actually reporting increasingly difficulties in recruiting people with the right skills. In general, there is a big challenge afoot in re-skilling workforces to be ready for this kind of new employment landscape. If we’re only punching with one fist and we’re only drawing on half our talent pool (because women are not well-positioned to take advantage of these opportunities), it will also be a drag on companies and economies. For example, in South Africa the STEM (science, technology, energy, and mathematics) university gender gap remains quite wide so despite the fact that South Africa – overall – has achieved gender parity in professional and technical roles (at the skills employment level there is gender parity).

However, in terms of new university graduates, now only 13% of STEM graduates are women and so indeed, in terms of equipping one-half of the potential labour force for the future for this new employment landscape of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, we do need to see more change and we do need to provide better mechanisms for women to also be in a better position to take advantage of the opportunities that this new developed market will bring.

Just explain that: STEM. What does that stand for?

It stands for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. It’s basically, the scientific fields’ knowledge that will be very much driving some of the technological progress that we’re predicted to see with the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

With only 13% of graduates in those fields being women, South Africa’s on the back foot and there’s a lot of work to be done. A country that is doing incredibly well on the African continent, is Rwanda. Now that’s number 5 in the world in this field, in gender equality. What lessons can be learned from other countries on the continent and indeed, anywhere from the Rwandan experience?

As you know, our index is not looking at actual levels of economic development. We are really looking at gender-specific gaps. In each one, there is a country that obviously was not at the income level of South Africa, and has somehow managed to make progress across all the four fields that we’re looking at – the economic sphere, the health sphere, the education and politics – without creating these big gaps in gender and women’s participation, in particular. Rwanda is the country with the highest number of female parliamentarians in the world – 64% of all Members of Parliament in Rwanda are women. We spoke about that a little bit earlier, I believe, so in terms of the policies that will be put into place; at some point, that will create a virtual cycle. You’ll just have more diversity of experience for the range of factors that affect people for example, in the economic sphere, and so we could expect that it would have some influence there.

Rwanda also does have a very high women’s labour force participation as well. As you mentioned, there are many advantages there and many strong things that a country such as Rwanda can draw on but even there, a challenge definitely remains in creating these high quality jobs that will be required in the Fourth Industrial Revolution for a country to be well-positioned there for both women and men. Maybe to some extent, some of the countries on the African continent are actually in a position that they have had an opportunity to observe some of the trends that maybe went wrong in some other regions in this regard. As labour markets on the continent are transforming as well, there is an opportunity to already be aware of these mistakes and gaps that have been made in other places, to make sure that you really have a very inclusive way of skilling both women and men for the Fourth Industrial Revolution and to have a workforce that is well-equipped for that.

Just to close off with: when you kicked off, you said it was going to take more than 100 years for the world to close this gender gap. Surely, that’s not affordable.

Yes. Clearly, we need to make progress. We need to accelerate and of course, at a minimum, I think everyone that is listening here today…we would like to see this happen in our lifetime. Certainly, this is unacceptable. As I was mentioning earlier, this is not a foregone conclusion. This is not fate. We are projecting this every year based on the average rates of progress that we’ve been seeing that the world has been making, and so this can be changed and this can be accelerated. Ultimately, it depends on both governments and the private sector, and all of us to contribute to that.