Eskom insiders tied to ghost vending scam behind soaring municipal debt

Key topics:

Eskom insiders ran ghost vending scams via breached online systems.

Municipalities billed for stolen power, inflating Eskom’s R109bn debt.

Flawed metering and billing let fraud go undetected for years.

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

Support South Africa’s bastion of independent journalism, offering balanced insights on investments, business, and the political economy, by joining BizNews Premium. Register here.

If you prefer WhatsApp for updates, sign up to the BizNews channel here.

By Jan Vermeulen

Large-scale electricity theft perpetrated by Eskom insiders could be contributing to billions of rands of municipal debt that local governments should rightly not have to pay.

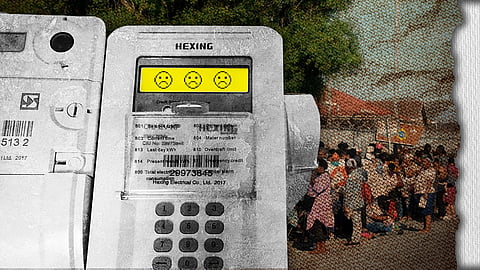

This is thanks to “ghost vending”, a fraudulent scheme that has seen billions of rands of prepaid electricity tokens generated, with Eskom collecting no revenue from them.

While the fraudulent units were generated using Eskom’s online vending system (OVS), it may not only have been Eskom Direct customers who stole prepaid electricity this way.

MyBroadband understands there is a workaround available to fraudsters with the clearance needed to access the OVS that would allow Eskom-generated tokens to be used on STS-compliant municipal prepaid meters.

A household consuming electricity this way would cause their municipality’s master meter to run up. The municipality would therefore have to pay Eskom for the electricity, even though the user had not paid for it.

Eskom first revealed that its online vending system (OVS) for prepaid electricity was breached in its last integrated report, published in December 2024.

It estimated that electricity theft, including illegal tokens and bypassed meters, cost it roughly R23 billion in revenue during its previous financial year.

However, MyBroadband has learned that the problem is much larger than Eskom is letting on, and that high-ranking individuals at the company are potentially involved.

When MyBroadband contacted Eskom for comment regarding whether the OVS breach and ghost vending in general impacted municipalities, it declined to answer on their behalf.

Tshwane, the metro home to South Africa’s administrative capital, dismissed the issue. Johannesburg’s City Power did not respond to a request for comment.

“The City of Tshwane operates on a real-time vending platform, therefore, there are no reported ghost-vendors in the city’s vending system,” a spokesperson for the Tshwane metro said.

Eskom’s municipal debt has grown exponentially over the past 12 years, with local governments and metros owing the power utility R109 billion as of February 2025.

In December 2024, the City of Tshwane signed a payment arrangement plan to settle its R6.7 billion debt to Eskom, with the last payment scheduled for March 2029.

Earlier this year, Tshwane announced that it had paid R1 billion towards its arrears and cleared a R4.7 billion VAT debt linked to a cancelled smart meter contract.

Joburg’s City Power and Eskom met with electricity minister Kgosientsho Ramokgopa on 24 June 2025 to resolve their debt dispute. They agreed that City Power would pay R3.2 billion over four years.

Big billing questions

In July, the South African National Energy Development Institute (SANEDI) published a report that raised concerns about billing accuracy, estimation processes, municipal debt, and the regulation of bulk power purchases in the country.

SANEDI was called on to assess the dispute between Eskom and City Power. It rejected City Power’s mock billing, found non-compliant estimation practices, and a net underbilling by Eskom.

“The analysis indicates a combination of overbilling and underbilling. The cumulative impact over these estimated sites observed a net underbilling impact of 142,798,857kWh,” SANEDI wrote.

It also identified procedural gaps on both sides of the dispute and systemic flaws on the part of Eskom and City Power.

The report showed that Eskom’s estimations failed to consider load-shedding effects and violated National Rationalised Specifications (NRS) 047 estimation standards.

At the same time, City Power’s check meters were often misconfigured, and its mock billing practices were found to be deeply flawed.

This lack of accuracy created an additional gap that allowed prepaid electricity thieves to escape detection.

At the same time, these metering problems make it difficult for metros like Johannesburg to conclusively show whether and how much money they were losing due to security flaws in Eskom’s systems.

A further indication of huge problems with prepaid electricity in South Africa is that City Power recently stopped postpaid to prepaid electricity meter conversions.

Johannesburg’s electricity distributor is investigating why some customers have stopped buying electricity after being migrated from postpaid billing to prepaid smart meters.

New prepaid meters becoming non-vending could be an indicator of broader illegitimate electricity use, illegal connections, meter tampering, or the use of fraudulent prepaid vouchers.

City Power also said other discrepancies cropped up on some accounts, including some not being accurately reflected in its systems after conversion.

These issues indicate that migrating people from postpaid to prepaid meters is not the silver bullet to electricity theft that many believed it was, and may actually be playing into the hands of a syndicate inside Eskom.

Compromise of the Eskom Online Vending System

Eskom introduced the online vending system (OVS) in 2008 to combat ghost vending using old offline credit dispensing units (CDUs).

Corrupt Eskom officials helped syndicates obtain the equipment, technical know-how, and system access needed to generate fake electricity tokens — first on CDUs, and later on the OVS.

University of Johannesburg research associate and forensic investigator Calvin Rafadi has explained that Eskom tried to recall its CDU machines when it launched the online vending system.

However, Eskom officials stole several of the machines from where they were kept in storage. They also obtained the disks and other equipment necessary to alter the electricity prices on the devices.

CDU-based “ghost vending” remained a problem long after the online vending system was launched, with law enforcement struggling to dismantle the criminal syndicate behind the theft.

In 2015, the Hawks announced the arrest of a Vereeniging woman suspected of being a crucial player in an illegal electricity voucher vending syndicate.

“Investigators are confident that they are close to catching those who are running this ghost vending syndicate,” police said at the time.

Six years later, in 2021, the Hawks, Eskom, and other law enforcement bodies announced the arrest of seven people suspected of being involved in a ghost vending syndicate.

“The syndicates reportedly operate in groups nationally and generate income of approximately R150,000 to R250,000 per day from illicit sales of electricity,” Eskom and the Hawks stated.

That amounts to between R54.8 million and R91.2 million per year in discounted illegal electricity tokens. Eskom’s revenue losses would be even higher.

“They are highly organised, well-equipped and closely networked and are difficult to track due to the fact that these machines do not transact on a network or at a single place, but are constantly roving.”

In 2023, the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) revealed that a former employee of Eskom had allegedly stolen a Master Vending Unit from the company.

Before he died, he allegedly turned ghost vending into a lucrative family business, generating over R36 million in illegal electricity tokens.

Because of how this fraud is perpetrated, Rafadi said Eskom was embarrassed to speak about it. This has allowed Eskom insiders and former employees to “run a parallel Eskom,” he said.

“We need to deal with the root cause — the managers inside Eskom who are involved,” said Rafadi.

Eskom’s response

When asked for an update on the ghost vending situation at Eskom, Group CEO Dan Marokane again said there have been positive developments, but they wouldn’t disclose details until their financial results.

“We have made tremendous progress in locking down the areas and access into ghost vending, both from a physical perspective and also our ability to trace and reconcile the three-way machine pattern OVS uses,” said Marokane.

He explained they look at what tokens the OVS shows have been generated, what comes through their customer care and billing system, and what Eskom’s financial system indicates.

“We are comfortable that we have made significant progress in this regard. We will detail a lot more when we release our financial results in a few weeks,” said Marokane.

“We are, of course, not where we want to be in that space. It is a very complex arrangement we’ve had to deal with, but in the last 12 months we’ve made tremendous progress.”

Marokane said they were working alongside law enforcement agencies, including the SA Police Service and State Security Agency. However, they could not comment other than confirming there were cases open.

*This article was originally published by MyBroadband and has been republished with permission.