Penny dreadfuls: Victorian thrills, horror, and the birth of popular fiction

Key topics:

Victorian penny dreadfuls: cheap, sensational horror, crime, and supernatural tales

Influenced modern horror, crime fiction, serialised stories, and pop culture

Reflected working-class interests, moral panic, and democratisation of reading

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

Support South Africa’s bastion of independent journalism, offering balanced insights on investments, business, and the political economy, by joining BizNews Premium. Register here.

If you prefer WhatsApp for updates, sign up to the BizNews channel here.

By Jen Isaac

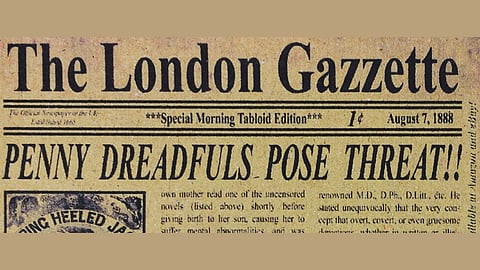

Horror and gore, shock and awe, lurid tales of sin and more – for an affordable price, you too could regularly escape the grim realities of the factory and find your imagination transported beyond the smog-filled streets of Victorian England’s urban pressure cookers. This is the story of the penny dreadfuls: they had the supernatural and the untamed, the demented and the depraved – and they were available for just a penny.

If you think they were cheap and nasty, you would be right. But if you dismiss them as only that, you’d have a lot to learn, and you’ve already forgotten too much.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1897 came long after. The vampire myth first burst into storytelling in one of the penny dreadfuls. Movies are still being made about characters like Sweeney Todd. Dick Turpin was the original anti-hero, and the peculiar blend of crime-fighting and the supernatural entrenched by comic-book heroes took not only its inspiration but its cue from the literary phenomenon that was the penny dreadful.

They emerged in Britain during the early 19th century, coinciding with the rise of literacy among the working class. As soon as the people could read, they did, but they did not read what they were instructed to. Instead, they turned to real storytelling fodder.

The rise of cheap printing technologies, such as steam-powered presses, made it easier to produce large quantities of printed material at low cost. Publishers saw an opportunity to cater to this new market of literate, working-class readers by creating affordable and easily digestible literature. penny dreadfuls filled this gap by offering thrilling stories that appealed to the imaginations of these readers, combining mystery, horror, crime, and adventure in serialised formats.

But don’t look down on them too quickly… everything you’ve ever read by Charles Dickens was first a serialised story. By the time he showed up, sure, things were more tame. Still, he owes them for their format.

Penny dreadfuls refer to both the price – one penny – and the “dreadful” or sensational nature of the content. Other terms for this genre included “penny bloods” and “shilling shockers,” depending on the price and intensity of the material.

Fresh stories arrived like the bodies left behind by a foul killer, weekly or bi-weekly. And they couldn’t wait for the next issue. Some of the most popular tales included:

Varney the Vampire: Written by James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, Varney the Vampire (1845- 1847) is one of the earliest examples of vampire fiction. Varney’s adventures mixed horror with tragedy, and the character influenced later gothic and vampire literature, including Dracula.

Sweeney Todd: The String of Pearls, published in the 1840s, introduced readers to the now-famous character Sweeney Todd, the “Demon Barber of Fleet Street.” Todd was a villainous barber who murdered his customers and passed their bodies to his accomplice, Mrs Lovett, who used the flesh to make meat pies.

Spring-Heeled Jack: A strange and mythical figure, Spring-Heeled Jack first appeared in penny dreadfuls in the late 1830s. Depicted as a ghostly figure capable of leaping great distances, his stories blended mystery, crime, and the supernatural. Superhero, anyone?

Dick Turpin: Turpin, a historical highwayman, was another recurring character in penny dreadfuls. His exploits were romanticised and exaggerated, turning him into a swashbuckling anti-hero rather than a mere criminal.

The appeal of these characters lay in their combination of thrills, mystery, and the supernatural, which often helped readers escape the harsh realities of Victorian life. Penny dreadfuls also frequently reflected the anxieties of the era, touching on fears related to urban crime, moral corruption, and the supernatural.

Despite the fact that penny dreadfuls were often dismissed as lowbrow literature, their enduring popularity demonstrated their ability to tap into deep cultural undercurrents and provide entertainment for a wide audience.

The penny dreadfuls were groundbreaking in their mass appeal. They targeted a demographic that was largely ignored by the more established publishing industry – the working-class reader. At a time when books and periodicals were typically expensive and catered to the middle and upper classes, penny dreadfuls democratised reading.

Additionally, penny dreadfuls paved the way for the development of popular genres such as crime fiction, detective stories, horror, and adventure. Many of the themes and tropes seen in later pulp fiction and modern-day thrillers can be traced back to the penny dreadfuls. The impact of these cheap publications can also be seen in the growth of serialised fiction, a format that continues to thrive in the television and streaming era.

Many middle- and upper-class Victorians viewed the publications as morally corrupting and intellectually bankrupt, proving that no matter where you find your pleasure in this world, some prude will find a reason to spoil it for you.

These horrible, wicked pamphlets were – obviously – promoting immorality and bad behaviour among the working class, particularly impressionable young boys. They glorified criminals like highwaymen and murderers, turning them into folk heroes. They feared that readers, especially young boys, would be inspired to imitate these figures. This concern fed into a broader moral panic about the impact of mass culture and cheap entertainment on public morals.

Like always, the more the upper castes and self-described authority figures fought against the phenomenon, the more popular it became. Various campaigns to ban or restrict the publication of penny dreadfuls took place, though these efforts were largely unsuccessful. Despite their low reputation, penny dreadfuls continued to thrive throughout the 19th century, remaining a staple of working-class entertainment.

Eventually, as literacy rates continued to rise, readers sought out more sophisticated reading material. The rise of the boys’ adventure genre, exemplified by works like The Boy’s Own Paper, provided more wholesome alternatives to penny dreadfuls. These new publications aimed to offer moral guidance while still providing adventure and excitement. One could argue that all that uppity, posh, boring stories would never have been given the time of day if the cheap and nasties didn’t foster a love of reading first.

Additionally, the introduction of half-penny and penny papers, such as The Daily Mail, offered readers inexpensive news and serialised fiction that was more socially acceptable than penny dreadfuls. The emergence of pulp magazines in the early 20th century also marked a transition from the penny dreadful format to a more polished and professionalised form of popular fiction.

Face it, the best reading you’ll ever do and ever did was done as a guilty pleasure. And although the penny dreadfuls faded from view by the early 20th century, their legacy lives on. Every time they end an episode on a cliffhanger – or you pick up a bestseller at the airport – know that your low-brow, offensive, cheap and nasty taste in stories is as old as literature itself. And as you just keep turning the pages, there’s something dark and dastardly waiting just for you, right after the next paragraph…