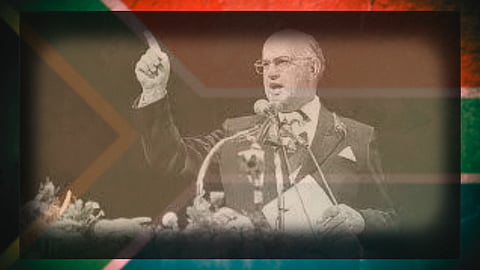

The 40th Anniversary of the PW Botha's Rubicon Speech: Dave Steward

Key topics:

PW Botha’s 1985 Rubicon speech signalled limited reform amid crisis.

Speech failed due to miscommunication, despite important policy shifts.

Current “national dialogue” echoes past crises, with leadership failures.

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

Support South Africa’s bastion of independent journalism, offering balanced insights on investments, business, and the political economy, by joining BizNews Premium. Register here.

If you prefer WhatsApp for updates, sign up to the BizNews channel here.

By Dave Steward

40 years ago PW Botha delivered his catastrophic Rubicon speech. Today, the ANC is convening a “National Dialogue” to discuss the multifold crises confronting South Africa.

At the beginning of August 1985, PW Botha’s worst nightmares of the “total onslaught” seemed to be coming true. There was unrest and violence throughout the country; South Africa was facing growing international sanctions; the Soviets were deepening their intervention in Angola and the economy was in crisis.

There was, however, a strong sense that the crisis could not be resolved by tougher security measures alone. The more “verligte” elements within the government – including the Department of Foreign Affairs – believed that only accelerated reform could address the growing storm of international outrage caused by the widely televised response of the security forces to the unrest. One of the central concessions that they advocated was the unconditional release of Nelson Mandela.

On 2 August PW Botha convened a meeting of government leaders at the “Sterrewag, a Military Intelligence facility in Pretoria, to discuss the growing crisis. Each minister was invited to express his views. Most were incoherent. Chris Heunis, the Minister of Constitutional Development, proposed a ‘Council of Cabinet Committees’ that would represent the interests of black South Africans in the ‘white area’ – but as extensions of the governments of the ten black states. PW Botha was strongly opposed to the establishment of a fourth ‘black’ chamber in parliament and rejected any idea that black South Africans should be included in the national or provincial executives. The meeting ended inconclusively – except that whatever the government decided would be announced in a major speech that President Botha would deliver in Durban on 15 August at the Natal Congress of the National Party. A number of ministers including Pik Botha and Chris Heunis, were invited to submit proposals for inclusion in the speech.

On 8 August Pik Botha flew to Vienna where he briefed the Americans and the British about President Botha’s coming speech. Chet Crocker, US Assistant Secretary of State for Africa, writes in his memoirs that Pik Botha was “at his Thespian best… walking out on limbs far beyond the zone of safety to persuade us that his president was on the verge of momentous announcements. We learned of plans for bold steps, and further thinking relative to the release of Mandela”.

The speech was duly delivered on 15 August in the Durban City Hall. Botha was clearly annoyed by the pressure that had been exerted on him by the “verligtes”. He warned of the danger of the unrealistic expectations and, in a long and rambling address, rejected any attempt by anyone to dictate solutions to the South African government. He insisted that he was “not prepared to lead white South Africans and other minority groups on a road to abdication and suicide.”

However, in an almost unnoticed sentence at the bottom of page 12 of the 20-page speech, he accepted the permanence of black South Africans in the so-called ‘white’ areas – and the need for their political accommodation in South Africa. “Should any of the Black National States therefore prefer not to accept independence, such states and communities will remain part of the South African nation, are South African citizens and should be accommodated within political institutions within the boundaries of the Republic of South Africa.” With this sentence, Botha accepted a common constitutional destiny for black and white South Africans and drew a line through the whole Verwoerdian ideology of Separate Development. He said that the future of black South Africans outside the National States would “ have to be negotiated with leaders from the National States, as well as their own ranks.”

Read more:

The full impact of the Rubicon speech became evident only the next day. Margaret Thatcher and President Reagan – who had been led to expect so much – were astounded, confused and deeply disappointed. Perceptions began to grow that South Africa was doomed to spiral downward toward chaos and conflict. South Africa’s opponents were jubilant; resistance to further draconian sanctions disintegrated – even in those countries – like the United States and United Kingdom – that were still trying to work for some kind of positive solution.

Ironically, the failure of the speech had little to do with a lack of content: the government’s decision to accept black South Africans in the so-called white areas as a permanent factor in South Arica’s constitutional future; the announcement of the imminent ending of the hated pass laws; and the expenditure of a billion rand on the upgrading of black communities; and willingness to negotiate with black South Africans about their future constitutional accommodation, were all important and saleable departures from the government’s previous positions.

The problem was not content – but communication – and particularly the absolute failure to plan effectively the communication of so important a statement. The most egregious error was the manner in which the speech was presold by Pik Botha and the Department of Foreign Affairs. The creation of such expectations was a fatal error. It was like asking an athlete to begin a 100-meter race from 100 meters behind the starting line.

Pik Botha regarded the Rubicon speech debacle as “one of the biggest lost opportunities ever.” Had it been seized; South Africa could have started the transformation process five years before its commencement in February 1990.”

This, however, represents a fatally flawed misreading of the situation confronting South Africa at that time:

In August 1985 the ANC and the SACP still believed that there might be a revolutionary victory and had accordingly not yet accepted the need for constitutional negotiations.

The South West Africa question was still unresolved. The Soviet Union was still supporting the intervention of tens of thousands of Cuban troops in Angola and would have exploited any sign of weakness by the PW Botha government.

The white electorate was not yet ready to accept negotiations with the ANC;

The government had no clarity about what its constitutional objectives would be in negotiations on the future of the country.

By the beginning of 1990 the situation had changed quite fundamentally:

Under Nelson Mandela’s leadership, the ANC had by 1987 accepted that there would be no revolutionary victory and that there would have to be negotiations;

Soviet intervention in southern Africa had ended following the 1988 Tripartite Accord between South Africa, Cuba and Angola. South West Africa was well on the road to independence;

The economy, though battered, was growing at 2,7%; and

The NP had accepted the idea of a constitutional democracy in which the rights of all South Africans would be protected by independent courts, economic realities and an international environment dominated by the Washington Consensus.

On 2 February 1990 FW de Klerk finally crossed the Rubicon.

Now, 40 years later, South Africans are once again facing a looming national and international crisis. Nelson Mandela’s heirs have proved to be corrupt, inept and blindly committed to a ruinous race-based ideology. On the 40th anniversary of the Rubicon speech it will be launching a “national dialogue” - (probably a monologue) - to discuss the country’s future.

However, we already held a genuine and truly representative national dialogue in the constitutional negotiations between 1990 and 1996. There was little wrong with the vision that was included in the preamble to the 1996 constitution or the foundational values in section 1. The problem is that they have not been honestly pursued - or honourably observed - in the intervening years.