Freedom under fire: How democracies are silencing speech - Ivo Vegter

Key topics:

Free speech is eroding in liberal democracies

Governments push censorship via laws, fines

Encryption, media, and academia under threat

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

Support South Africa’s bastion of independent journalism, offering balanced insights on investments, business, and the political economy, by joining BizNews Premium. Register here.

If you prefer WhatsApp for updates, sign up to the BizNews channel here.

By Ivo Vegter*

There was a time when freedom of speech was a central premise of liberal democracy.

The ability to criticise, or poke fun at, authority, to raise controversial political questions, and to engage in public debate without fear of censorship or retaliation, is a cornerstone of an open democratic society. It isn’t just about saying what you want, but about cherishing the mechanism that holds governments accountable, exposes corruption, resists authoritarianism, and fosters political and economic progress.

It symbolises that reason and tolerance are the virtues upon which freedom and growth are built. It stands in contrast with the autocrat’s need to control and suppress ideas that challenge their authority.

It was a well-worn stereotype that in unfree countries, run by communists or tinpot dictators, you had to watch what you said and where you said it, because expressing the wrong opinion could bring jackboots to your door.

Being tried and sent to the gulag conferred a badge of respectability upon the ideas of authors, scientists or political figures. If Big Brother tried to silence you, then what you said must be worth hearing.

In recent years, however, supposedly liberal democracies have increasingly tried to claim control over speech.

Race to the bottom

The internet and social media at first promised a world in which everyone could have their say, could be heard, and could freely associate with others of a like mind no matter where they lived.

It spawned millions of special-interest groups, catering to specialist academic pursuits, niche hobbies, literary or entertainment fandoms, socio-political interests, medical problems, psychological difficulties, lifestyle habits, sexual kinks, hard-to-find parts or materials, religious communities, do-it-yourself tips, pressure-group organising, home cooking, and kittens.

Finally, distance no longer divided us. Governments and corporations could no longer gate-keep information and communication. It promised to be the ultimate medium for free expression.

Yet it came with its dark sides.

It led to a dumbing down of public information.

Between elevating voices that had no business being elevated, the financial kneecapping of professional journalism, and the commercial click-bait race to the bottom, we discovered that when you give a billion monkeys typewriters, you don’t get the collected works of Shakespeare. You get a mashup of Benny Hill and Jerry Springer, but less well-scripted.

Emotions, feelings, and cheap laughs at the expense of others have replaced logical reasoning, critical thinking and quiet contemplation.

The internet didn’t make us smarter by putting all the world’s knowledge at our fingertips. It made us stupid.

James Marriott, a writer at The Times, calls it, “The dawn of the post-literate society”. His essay is well worth reading, unless you read only short and cheerful things.

Bad information

For governments and regulators, the triggers to becoming more censorial… (does anyone in Gen Z still know that “censorious” would be the wrong word here, because it does not mean “inclined to censorship”?)

The triggers to becoming more censorial have been concerns about dis- and misinformation spread during the Covid-19 pandemic, revelations about hostile foreign disinformation campaigns aimed at destabilising countries and influencing their elections, the spread of advocacy for hate and prejudice, and the rising threat of political radicalisation that leads to violence.

These triggers are closely related to the dumbing down of the internet. The decline of critical thinking, the shortening of attention spans, the rise of outrage bait, and the ease with which bad information spreads conspire to make misinformation, disinformation and radicalisation more dangerous.

Politicians of all stripes exploit the visceral fear of the most extreme threats to public safety – like terrorism or child sexual abuse material – to justify broad interventions to monitor and limit online speech.

They also, egged on by the clamouring of censorious prudes (meaning narrow-minded people who are “prone to censure, moral judgement, or perfunctory condemnation”), take a “think of the children” approach to adult content, which gives them further excuses to police internet use and surveil citizens.

Read more:

Bad encryption policy

This is leading even nominally free countries to expand their suppression of free speech, both by direct action and by indirect manipulation of communication platforms.

In the UK, Apple no longer offers its customers end-to-end encryption of their cloud data, because the alternative would be to offer the UK authorities a backdoor that would have enabled them to access the encrypted data of every Apple user in the world.

Without end-to-end encryption, data is vulnerable not only to government surveillance, but also to corporate misuse and to malicious hackers. And they will use it.

To avoid breaking end-to-end encryption, the European Union is considering “chat control” legislation that would allow “client-side scanning”. Services that offer end-to-end encryption, such as ProtonMail or Signal, would be required to scan content on the client’s device before encryption and compare it against a government-provided list of hashes of prohibited content (such as known child abuse imagery, abusive language, or, well, anything the government in its infinite wisdom wishes to put on that list). If a match is found, it would report the user to the authorities.

This does not avoid breaking end-to-end encryption: it breaks it at one end, rather than in the middle or on the other end. It has all the same drawbacks as backdoors. There is no way to control what governments will consider reportable material. At first, it will be egregiously criminal stuff, but once the access is available, it will increasingly be used for policing, for “fishing expeditions”, and political speech suppression.

Bad moderation policy

Legislation like the Digital Services Act in the EU, designed to “govern the content moderation practices of social media platforms”, places increasingly rigorous obligations on all content service providers to moderate content. Failure to comply comes with business-threatening fines of up to 6% of global annual turnover.

The Online Safety Act in the UK serves a similar purpose. It places a “duty of care” on content platforms to remove illegal content as well as “legal but harmful” content, which is a vague and dangerously broad phrase. It also levies massive fines, of 10% of annual turnover.

The UK law also requires platforms to scan encrypted content, though the UK government admits that this clause is “non-operational” because the technology to scan encrypted messages without breaking privacy doesn’t yet exist. Hint: it never will, because privacy is the purpose of encryption, but it certainly exposes the intention of the UK government to somehow, someday, defeat encryption.

Australia, too, is mulling a law that would fine platform operators 5% of their revenue for failing to counter certain types of “misinformation”.

The danger here is twofold. Governments are certainly entitled to set narrow limits on what constitutes illegal content – such as incitement to public violence, conspiring to commit serious crimes, making credible threats to public or individual safety, or distributing child abuse material.

However, governments are neither competent nor entitled to determine what constitutes “misinformation”, “disinformation” or “harmful content”. Governments, which comprise politicians (who lie) and bureaucrats (who do what they’re told by politicians), are not arbiters of truth, nor of vague moral harms.

Wider danger

The wider danger, however, is that by making platforms and communication service providers liable for user behaviour, governments not only get compliance, but also incentivise them to go much further than they are legally required to go, just to be safe. Their interest is commercial; if defending free speech doesn’t pay, they won’t defend it.

Their artificial intelligence (read: unintelligent) moderation bots and outsourced, minimum wage, poorly trained, overworked and often traumatised human content police are already on a hair trigger.

They respond to take-down requests by taking down first and asking questions later, and have no incentive to make it easy to challenge over-zealous moderation.

By shifting the onus to private companies, governments can also neatly sidestep their own constitutional limitations. Private platforms, after all, can implement moderation policy however they like, and politicians can claim plausible deniability.

Other suppression tactics

The legal tools available to politicians to control speech vary from one country to another, and depend on constitutional protections of rights and freedoms.

Traditionally, the US has been a beacon of liberty on free speech, with protections that brook almost no limitation.

Its Supreme Court upheld the free speech rights of dinkum Nazis when they wished to march through a largely Jewish neighbourhood, and upheld the right of a Ku Klux Klan member to call for “revengeance (sic)” against Jews and black Americans, because it was not likely to incite imminent violence.

These precedents echoed the views of true free speech advocates like Salman Rushdie, who said, “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist,” and Noam Chomsky, who said, “If we don’t believe in freedom of expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all.”

Read more:

Yet free speech in the US is also under grave threat from the present administration, despite its rhetoric to the contrary. It has vowed to target the “radical left”, which officials described (falsely) as “a vast domestic terror movement”.

The US president has personally sued media houses across the political spectrum that published news that was in the public interest, but harmed him politically, for improbably large amounts ($10 billion, in one case). He has threatened others with yanking their operating licences, or withholding regulatory approval for merger and acquisition activity.

Being commercial organisations, some of these organisations have chosen to settle, handing the government a political victory.

He has used the same tactics against universities that permit speech that is inconsistent with the ideology of the party in power.

He has fired, or caused to be fired, government employees who don’t toe the political line, and applauded private companies that fired or suspended people for offending his fragile ego or contradicting his political views.

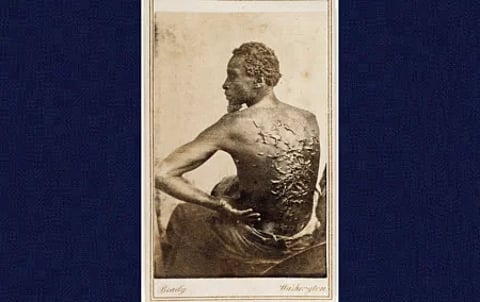

He has directed museums and facilities like national parks and monuments to remove historical exhibits that reflect the US in a negative light, much like the Ministry of Truth did in George Orwell’s 1984. (The 1863 photo of a slave’s scourged back that accompanies this article is an example of material that has been declared undesirable.)

These actions have a chilling effect on speech. If criticism of a government official can now earn you a multi-billion dollar lawsuit or regulatory vengeance by federal agencies, then you’re going to be much more cautious with what you let your journalists write, or what you let your professors say.

This fundamentally undermines the independence of academia and the media, which are foundational to free expression in a free democracy.

Problems with policing speech

The problems with government policing of public expression are manifold.

One issue is that the tools they use cannot be restricted only to speech that is problematic or criminal. To detect incitement, or material that endangers children, or extremist plotting, one must monitor all online communication. To restrict access to adult content, one must require ID access to all online content, including social media.

Since encryption, proxy servers, or virtual private networks could circumvent government monitoring systems, they must be prohibited, or given backdoors that police agents can use for surveillance.

Another issue is that if government agents have access to private communication, so does everyone else. If there is a backdoor, hackers can and will find it and exploit it.

Limiting the use of encryption for chats so the government can monitor “radicalisation” or “extremism”, or so they can age-restrict adult content, also undermines its use for any other purpose. How would the government know who you’re talking to, and whether privacy for that conversation is a legitimate demand? It can’t, which means online banking, or communicating with your lawyer, therapist or doctor, are also compromised.

There simply is no technical way to permit encryption for one form of internet communication while backdooring or prohibiting it for another.

Spill-over

Content standards applied in developed economies also tend to spill over internationally.

For multinational content or communication companies, it makes little commercial sense to carve out country-specific policies when most of the users are in Europe or the US. Ultimately, they’ll simply err on the side of caution, and restrict free speech everywhere. For the corporations to be safe from ruinous fines, they cannot permit legitimate speech that challenges authority or offends the political class.

These global trends have serious implications for our own fight against the egregious flaws in South African laws aimed at controlling public information, such as the Protection of State Information Bill, the Film and Publication Amendment Act, the Regulation of Interception of Communications Act, the Prevention and Combating of Hate Crimes and Hate Speech Bill, the Cybercrimes Act, and the pandemic-era laws that prohibited the publication of any information about Covid-19 that contradicted government-approved messaging.

How can we claim that the government does not have a right to conduct mass surveillance, or to access private communication without due cause, or break encryption, or criminalise speech for merely being offensive, or require pre-certification for online content, or prohibit the use of widely available network security tools just because they can also be used for malicious purposes, if the standard-bearers of liberal democracy around the world are doing the exact same?

The world is barrelling headlong towards a new era in which expression of all kinds will be directly, or indirectly, restricted. Threats of enormous fines or regulatory retaliation are co-opting the corporations that provide media, content and communication facilities in service to government censors.

Chilling free speech has consequences: it creates space for politicians to create “truth” out of thin air and manipulate public opinion to serve their ideological goals.

It creates an environment in which power can grow unchecked, and corruption can go unreported.

It creates a world in which we all watch what we say, lest we offend the AI bots or moderators of our favourite communication platforms, or worse, offend our political overlords and provoke retaliatory action against us, our companies, or our employers.

For nascent democracies like ours, that are trying to build a free society in which the power of the state is limited and the rights of the people are protected, the fall of free speech in countries that once were beacons of liberty sets a terrible example and a dangerous precedent.

*Ivo Vegter is a freelance journalist, columnist and speaker who loves debunking myths and misconceptions, and addresses topics from the perspective of individual liberty and free markets.

This article was first published by Daily Friend and is republished with permission.