LONDON — Former Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan loved to point foreign investors towards the South African economy’s famous resilience. Were he still around, he’d need to find a new line because president Jacob Zuma has succeeded where the blundering of all his predecessors failed. As independent economist Azar Jammine explains in this superb analysis of the official GDP figures for the first quarter of 2017, bad politics finally caught up with the country and has now smashed the economy’s resilience. The breaking point was reached before, but was most clearly illustrated in Zuma’s midnight cabinet reshuffle when Gordhan was fired. The blunders began soon after his ascension to the presidency in May 2009. Since then this ill equipped and deeply compromised president has expanded State spending while simultaneously attacking and eventually alienating a previously loyal tax base. Overlaying all this has been Zuma’s promotion of wide scale plundering of state resources by cronies like the Indian immigrant Gupta family. The evidence is overwhelming. Yet the majority of the ANC’s top brass still stand by the economy’s one man wrecking ball. If you thought education was expensive, try ignorance. – Alec Hogg

By Azar Jammine*

Based on monthly data for mining, manufacturing and electricity production, as well as retail and wholesale trade sales, the consensus was that a marginal positive growth rate will have been achieved by the economy in the 1st qtr of 2017, reflecting an improvement from the negative -0.3% q-o-q annualised growth recorded in the final quarter of 2016.

Given that a negative growth rate would have been followed by a positive growth rate in the subsequent quarter, there was relative confidence that a technical recession, defined as two successive quarters of negative q-o-q growth, will have been avoided.

The vast majority of economists, including ourselves, had anticipated positive growth in the 1st qtr of 2017, mainly on account of the steep recovery in the mining production figures, as well as the knowledge that the drought conditions in the summer rainfall regions of the country had dissipated and would see some recovery in agricultural output. Improvements in mining and agricultural output did indeed materialise.

Q-o-q annualised growth in GDP of mining recovered steeply to 12.8% in the 1st qtr, from -11.5% in the 4th qtr of 2016. Similarly, q-o-q growth in agricultural GDP rose strongly, to 22.2% in the 1st qtr of 2017, from -0.1% in the 4th qtr of 2016 and negative growth rates in the preceding eight quarters.

What was not expected was contraction in every sector outside of mining and agriculture

The problem was that every other sector of the economy posted a significant contraction in the 1st qtr of 2017, something that had not been anticipated.

Excluding mining and agriculture, the q-o-q rate of growth in the economy was a heavily negative -2.3%, compared with positive such growth rates throughout last year and 0.8% in the 4th qtr of 2016 specifically.

The most severe contraction took place in respect of the retail and wholesale trade, accommodation and restaurant sector which saw annualised growth falling to -5.9% in the 1st qtr, from a positive 2.1% in the final quarter of last year.

However, one also saw the contraction in manufacturing continuing for a third quarter in a row, to -3.7% in the 1st qtr, from -3.1% and -3.3% in the preceding two quarters.

Annualised GDP in construction, incorporating building and civil engineering, contracted by -1.3% compared with marginally positive figures for the whole of last year. GDP growth in transport and communication came in at a negative -1.6% in the 1st qtr, from a positive 2.6% in the preceding quarter.

The biggest shock was the negative growth in the GDP of the largest sector in the economy, viz. financial services and real estate, to -1.2% in the 1st qtr, from positive growth rates since the global financial recession. Even the personal services sector recorded marginally negative growth, of -0.1%.

Finally, the GDP of general government also contracted, by -0.6%, from low positive growth rates through the whole of last year. This reflected cutbacks on the part of government in employment and spending in order to meet fiscal consolidation targets required to avoid further credit ratings downgrades.

Read also: How markets will react to an economically illiterate president – Jammine

On a y-o-y basis, GDP growth excluding agriculture and mining declined to just 0.3% in the 1st qtr of 2017, from 1.3% in the final quarter of last year. This represented the lowest y-o-y growth rate in GDP excluding agriculture and mining since the global financial recession.

Y-o-y growth in GDP increased slightly to 0.6% in the 1st qtr of 2017, from 0.4% in the 4th qtr of 2016.

(The seasonal adjustment seems to have played an important role in depressing the q-o-q seasonally adjusted growth in GDP. Clearly there were strange anomalies with Easter having fallen into March last year, but into April this year. The same anomalies seem to have impacted on exports and imports. Even though the trade balance improved substantially in the 1st qtr, the seasonally adjusted growth in exports fell sharply whereas that of imports was much stronger.)

Contraction in consumer spending at the heart of slowdown

Reflected in the steep contraction in the retail and wholesale trade and tourism sector, it would appear as if the biggest driver of the contraction in GDP in the 1st qtr was the steep decline in the growth of household consumption expenditure, which accounts for more than 60% of GDP.

Consumer spending of households declined by -2.3% on an annualised basis in the 1st qtr of 2017 from a positive 2.2% in the 4th qtr of 2016 and an average growth rate of 0.8% in 2016 overall.

Even though inflationary pressures had begun receding as a result of reduced rates of increase in food prices associated with the ending of the drought and the knock-on effects of a strong Rand in reducing the rate of increase of the cost of imports, households appeared to cut back on spending materially.

One suspects that uncertainty on the political front and the decline in consumer confidence that this contributed towards, finally caught up with household spending patterns.

In recent weeks we had already identified a significant reluctance on the part of households to borrow money. This was reflected in part by a steep decline in the rate of household debt to disposable income. Now we see that this reluctance to borrow has translated into a falloff in consumer spending.

Spending declined in several categories, including food (-0.7%), alcoholic beverages and tobacco products (-0.3%), clothing (-0.7%), furniture (-0.3%), transport (-0.7%), recreation (-0.4%) and restaurants (-0.2%). Only in the case of housing (+0.1%), health care (+0.2%) and communications (+0.2%), was any semblance of growth recorded.

It is just conceivable that the growth in the retail sector was damaged by statistical factors. In March last year there were a spate of public holidays which may have elevated the scale of retail trading so that one might have been comparing against a high base of sales a year ago.

Read also: Ratings agencies have left us swimming, but gasping for air – Jammine

Nonetheless, the decline in GDP growth was further exacerbated by significant cutbacks in spending by the government itself, as it attempted to curtail the growth in its expenditure in the face of falling tax revenues so as to avoid an increase in the budget deficit and public debt.

Such fiscal austerity was invoked in order to avoid further credit ratings downgrades. Unfortunately, the Cabinet reshuffle at the end of March scuppered all such attempts at providing confidence of commitment to fiscal responsibility.

Furthermore, looking ahead, one cannot hold too much hope for any major pickup in consumer spending given the fact that cumulative increases in taxation incorporated in the February Budget amounted to 1% of overall household consumption expenditure.

Only encouragement is resilience of fixed capital formation

If there was one source of encouragement in the latest figures it relates to fixed capital formation. Last year the -3.9% contraction in fixed capital formation on the back of declining business confidence lay at the heart of the fall in GDP growth to just 0.3%, its weakest performance since the global financial recession.

However, in the 1st qtr of 2017 fixed capital formation managed to eke out a 1.0% q-o-q seasonally adjusted growth rate, coming on the back of a similar 1.7% improvement in the 4th qtr of last year.

This resilience does need to be seen in the context of a shocking performance in fixed capital formation in the first three quarters of last year and represents a bounce off an extremely low base. Nonetheless, one can at least derive some solace from the marginal improvement.

Specifically, there was a slight improvement in residential building (+0.9%) and investment in machinery and equipment (+2.5%), even though they were contractions in investment in non-residential building activity (-1.1%), civil engineering (-1.0%) and transport equipment (-0.8%).

However, one fears what these trends will look like in the wake of the damaged business confidence caused by the Cabinet reshuffle at the end of March and the subsequent credit ratings downgrades. The latter have also made access to funding from banks that much more difficult.

Also somewhat sobering is the decline in annualised growth of exports of goods and services, to -3.2% in the 1st qtr, from 12.5% in the 4th qtr of last year. The decline in the growth of exports was far steeper than the corresponding decline in growth of imports from 6.1% to 3.2% respectively.

This raises questions with regard to the compatibility of these figures with the improvement in the balance of trade as reflected by the SARS trade figures on a monthly basis in the 1st qtr.

Likelihood of 1% growth in 2017 severely dented

We have been relatively upbeat about the possibility that overall economic growth in 2017 will come in stronger than it did in 2016.

All along the line we have suggested that the credit ratings downgrades have indeed reduced economic growth potential, but would nonetheless still accommodate an improvement in growth from 0.3% last year to at least 1% this year. Unfortunately these latest figures dent such relative optimism severely.

Given that the poor GDP figures for the first quarter related to an environment prior to the Cabinet reshuffle and subsequent credit ratings downgrades means that if anything, the environment for economic growth would have deteriorated even further in subsequent quarters.

Read also: Azar Jammine: Making sense of Rand’s whipsaw – why it is set to drift lower

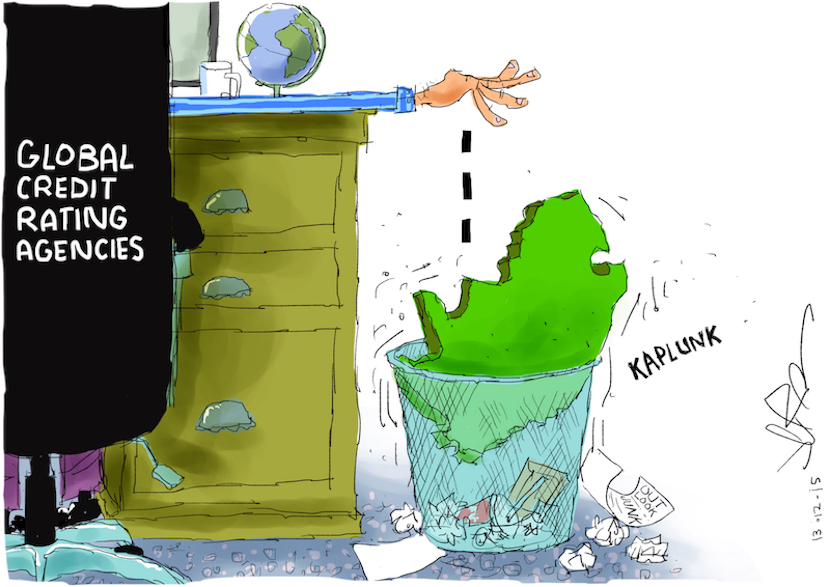

Attainment of 1% growth rate in 2017 now looks forlorn. This has significant negative implications also for the avoidance of further credit ratings downgrades and a worst-case scenario which sees South African government bonds falling out of the World Government Bond Index, with negative implications for the Rand, inflation, interest rates and economic growth.

Ratings agencies are likely to see these latest figures as jeopardising the ability of government revenue to increase sufficiently to prevent the public debt to GDP ratio from rising significantly further.

As such, the latest low growth figures increase chances of S&P Global and Moody’s downgrading South Africa’s credit rating to junk status when they review the credit ratings again in November. As a result, prospects for economic growth in 2018 have been dealt a severe blow.

Possibility of rate cuts may have been increased

From a monetary policy perspective, the possibility of a reduction in interest rates sometime later this year has been enhanced by the latest poor GDP figures. The Reserve Bank knows only too well that lower interest rates are not the panacea for improving growth, but may feel obliged to accommodate pressure for some interest rate relief.

From a monetary policy perspective, the possibility of a reduction in interest rates sometime later this year has been enhanced by the latest poor GDP figures. The Reserve Bank knows only too well that lower interest rates are not the panacea for improving growth, but may feel obliged to accommodate pressure for some interest rate relief.

The fact that the quarterly compensation of employees figures which accompany these latest GDP figures show a marked reduction in the rate of growth of such compensation to just 6.0% in the 1st qtr of 2017, from 7.0% in the preceding quarter and 8.2% in the 1st qtr of 2016, illustrates the manner in which inflationary pressures are receding even in respect of workers demanding and accepting lower pay increases in the face of fears of retrenchment. This logic may be used as rationalisation for some interest rate relief.

On the other hand, if the Bank sees these figures as implying an increased risk of credit ratings downgrades, then of course it may yet hold off reducing interest rates.

On the whole, however, we believe that the possibility of interest rate reductions over the next couple of quarters has been enhanced. Unfortunately this is not really good news because it is a function of really bad news.

- Azar Jammine is the chief economist at Econometrix.