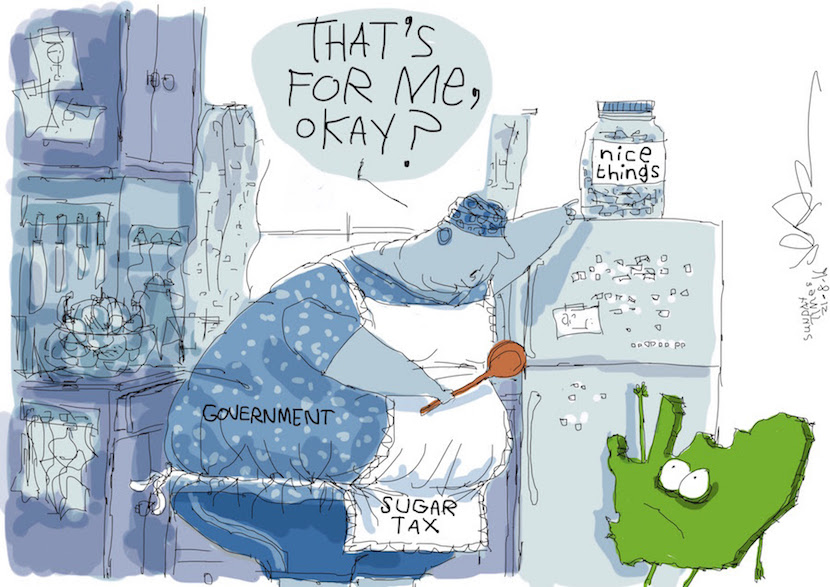

The main purpose for government’s introductoin of a sugar tax is to reduce obesity levels. And the two have apparently been linked through a model created in 2014. But Anthea Jeffery questions this in the piece below, and asks how conclusions can be drawn on a model that has five unproven assumptions. The debate for, and against a sugar tax also opens up the idea of a ‘nanny state’, something that some say should be avoided at all costs. While others are concerned the sugar tax is more of a smoke screen or ‘front’ to increase government revenues (for self-promoting projects) than a goal to cut down obesity levels in the country. what do you think? – Stuart Lowman

By Anthea Jeffery*

The National Treasury plans to introduce a roughly 20% excise tax on all sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) that contain added as well as natural sugar. The likely yield from the tax – based on 2015 sales figures for the SSBs to be subjected to the tax – will be roughly R10.5bn a year. The burden of the tax will also fall most heavily on the poor, who spend more of their income on food and drink than the rich.

According to the Treasury, the primary rationale is not to increase the government’s tax take, but rather to help overcome obesity. Moreover, since obesity is more prevalent among the poor, the resulting reduction in obesity will benefit the poor the most, so offsetting the impact of an admittedly regressive tax.

However, if this compensating benefit does not transpire, the tax will simply impose an increased economic burden on those consumers who are already the hardest pressed.

The Treasury indicates that a 20% SSB tax will reduce obesity by 3.8% among men and by 2.4% among women. As evidence of this, it cites a ‘mathematical model’ developed in 2014 by Professor Karen Hofman of Wits University.

According to this model, ‘a 20% tax is predicted to reduce energy intake by about 36kJ per day, while obesity is projected to decrease by 3.8% in men and 2.4% in women’. Hence, ‘the number of obese adults would decrease by over 220 000’.

However, the model has little hard data to support it. Instead, it rests primarily on five unproven assumptions, none of which is likely to hold true in the real world.

First, the model assumes that a 20% tax on SSBs will result in a 20% increase in the price of SSBs. This ignores the fact that producers and retailers could choose to absorb some of the burden of the tax, so as to keep prices down and help maintain sales.

Second, it assumes this 20% price increase will result in a major reduction in SSB consumption. However, consumers could shift to cheaper brands or cheaper outlets, or cut back on other items, so as to maintain their purchases of SSBs at much the same levels.

Third, the model assumes that this reduction in SSB consumption will lead to an average reduction in daily energy intake of 36kJ. But consumers could easily shift to other sugary products not subject to the tax – which means their overall energy intake will not come down.

Fourth, it assumes that this mooted reduction in daily energy intake will be enough to result in significant weight loss. However, 36kJ a day is a small amount, representing less than 1% of the recommended daily energy intake of a child or adult man.

Fifth, the model assumes that these reductions in body weight will be enough to reduce the prevalence of obesity in South Africa by the percentages it states – the basis for which is not adequately explained.

Read also: Bloomberg View: Sweet and sour notes on ‘sugar tax’

The projections in the model also vary more widely than the Treasury acknowledges. The model in fact estimates that a 20% SSB tax will result in a reduction in daily energy intake of anything between 9kJ and 68kJ, with an average of about 36kJ. So even a 36kJ reduction may not be attained and the diminution in energy intake – even if all the model’s assumptions hold true – could be as little as 9kJ a day.

The model further estimates that the resulting decline in obesity prevalence among men could vary from 0.4% to 7.2%, 3.8% being the average of these figures. Similarly, obesity prevalence among women could come down by anything between 0.3% and 4.4%, 2.4% again being the average.

Hence, the decline in male prevalence could be as low as 0.4%, which would reduce the number of obese men by 16 060, as the model acknowledges. In addition, the reduction in female prevalence could be 0.3%, which would reduce the number of obese women by 16 550, it says.

Read also: Sugar tax – a ‘sin tax’ that could help fat people get thin?

If these more conservative projections are fulfilled, the introduction of the SSB tax could see the number of obese adults come down by some 32 600. This is very different from the figure of ‘over 222 000’ which the Treasury has emphasised.

Such small gains in the fight against obesity – which will be achieved, only if all of the model’s assumptions in fact hold true – hardly warrant the extraction of another R10.5bn in tax from already struggling consumers.

The model is similar to various other academic studies that make equally unproven assumptions about sugar taxes and reduced obesity. Yet, as the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA) in the United Kingdom points out, a systematic review of some 880 studies dealing with the assumed link has found little evidence of any causal connection.

Writes the IEA: ‘There is a striking contrast between theoretical studies, which generally predict that such taxes “work”, and studies of hard data in places that have actually implemented them, which generally show the opposite. Lacking real world evidence that sugar taxes are effective as health measures, campaigners continue to cite findings from crude economic models which do not adequately account for the ability of consumers to choose cheaper or discounted brands, to shop at cheaper shops, or to switch to alternative high-calorie food and drink products.’

Writes the IEA: ‘There is a striking contrast between theoretical studies, which generally predict that such taxes “work”, and studies of hard data in places that have actually implemented them, which generally show the opposite. Lacking real world evidence that sugar taxes are effective as health measures, campaigners continue to cite findings from crude economic models which do not adequately account for the ability of consumers to choose cheaper or discounted brands, to shop at cheaper shops, or to switch to alternative high-calorie food and drink products.’

In addition, a 2014 study by the McKinsey Global Institute of 44 anti-obesity interventions around the world found that sugar taxes are generally ineffective in countering obesity, which has complex and wide-ranging causes. Yet sugar taxes get by far the most media attention, helping to skew debate and encouraging policy makers to embrace them. That these taxes yield useful amounts of revenue is also, of course, why governments tend to favour them.

In inviting comments on its SSB tax proposal, the Treasury has stressed that it will respond solely to ‘evidence’ and not to ‘speculation’. This is ironic, for the model on which it rests its claim that the tax will reduce obesity has little evidence to back it up – and relies primarily on speculation and assumption.

- Anthea Jeffery is head of Policy Research at the Institute of Race Relations. Jeffery is also the author of People’s War: New Light on the Struggle for South Africa. You can follow IRR on Twitter @IRR_SouthAfrica.