Berkshire AGM transcribed: Antecedents who shaped genius of Buffett, Munger

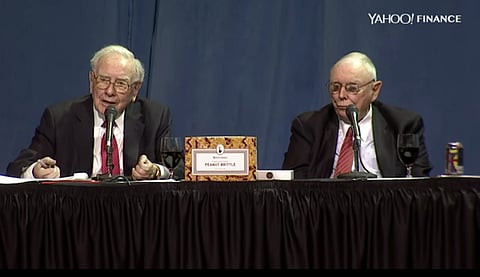

Questions posed by Berkshire shareholders at the AGM often stray into the personal philosophies of the principals, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger. But rarely do they open the door for the discussion which dominates this segment of the transcript – memories about the antecedents whose guidance shaped the duo into the perfect capitalists. Warren and Charlie are at their best when freewheeling, as they do here when reminiscing about their youthful years working in Buffett & Sons, the Omaha grocery store run by Warren's super-conservative grandfather Ernest. Lessons learnt from this humble establishment have served the two Midwestern great-grandfathers so well. – Alec Hogg

Smart investing is helped by calculating of the intrinsic value of the company you want to buy into – a concept that can be rather confusing. Warren Buffett says a business is only worth the cash that it will generate between now and "judgement day" – he uses 10 years – so the nub of the calculation is based on the free cash flow the business produces, also known as "owner earnings". In this segment's opener Buffett shares some details about Berkshire's own numbers, addressing recent criticism around the company's sizeable deferred tax liability…..

WARREN BUFFETT: I don't have the figure but let's just assume that's $60bn of unrealised appreciation and securities, well then there would be $21bn of deferred tax. That isn't really cash that's available. It's just an absence of cash that's going to be paid out until we sell the securities.

Some arises through bonus depreciation…..the Railroad will have depreciation for tax purposes that's a fair amount higher than for book purposes. But overall I think of the cash flow of Berkshire as a practical matter relating to our net income plus our increase in float, assuming we have an increase. Over the years float has added $80bn plus to make available for investment beyond what our earnings allowed for – that's the huge element. We're going to spend more than our depreciation in our businesses primarily being number one because of the railroad (BNSF) and Berkshire Hathaway Energy are two entities that'll spend quite a bit more than depreciation in all likelihood for a long, long, long, long time. The other businesses, unless we get into inflationary conditions, won't have a huge swing one way or the other.

Our earnings, not counting capital gains around $17bn plus change in float, is the net new available cash. But of course we can always sell securities and create additional cash or we can borrow money and create additional cash. It's not a very complicated economic equation at Berkshire. People for a long time didn't appreciate the value of float. We kept explaining it to them and I think they probably do now.

The big thing, the goal, what Charlie and I think about, that we want to add every year, is the normalised earning power per share of the company. We think we can do it. We have retained earnings to work with every year to get that job done. Sometimes it doesn't look like we've accomplished much and other years something big happens. We don't know ahead of time which year is going to be which. Charlie?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, there are very few companies that have ever been similarly advantaged. In the whole history of Berkshire Hathaway we've lived in a torrent of money and we were constantly deploying it and dispersed assets and we were wising up as we went along. That's a pretty good system. We're not going to change it.

WARREN BUFFETT: It's allowed for a lot of mistakes. That's the interesting thing. American business has been good enough that you don't have to really be smart to get a decent result. If you can bring a little bit of intellect then you should get a pretty good result.

CHARLIE MUNGER: What you've got to do is be aversive to the standard stupidities. If you just keep those out, you don't have to be smart.

What has allowed you to think ahead of the crowd; what obvious truth presents itself so clearly to you, but many would fervently disagree with?

WARREN BUFFETT: I owe a great deal to Ben Graham in terms of learning about investing and I owe a great deal to Charlie in terms of learning a lot about business and then I've also been around. I've spent a lifetime looking at businesses and why some work and why some don't work. As Yogi Berra said, "You can see a lot just by observing" and that's pretty much what Charlie and I have been doing for a long time, and you do. I would say it's important to recognise what you can't do. We may have tried the department store business and few things, but we've generally tried to only swing at things in the strike zone and our particular strike zone. It really hasn't been much more complicated than that.

You do not need the IQ in the investment business that you need at certain activities in life but you do have to have emotional control.

We see very smart people do very stupid things and it's fascinating how humans do that. Just take the people that get very rich and then leverage themselves up in some way that they lose everything. They are risking something that's important to them for something that isn't important to them. Well you could say you can figure that one out in first grade, but people do it time after time and you see that constantly – self destructive behaviour of one sort or another. I think we've probably – and it doesn't take a genius to do it – avoided the self destructive behaviour. Charlie?

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, it's just a few simple tricks that work well and probably you've got a temperament that has a combination of patience and opportunism in it. I think that's largely inherited although I suppose it can be learned to some extent. Then I think there's another factor that accounts for the fact that Berkshire has done as well as it has is that we're really trying to behave well. I had a great-grandfather, when he died the preacher gave a talk and he said, "None envied this man's success so fairly won and wisely used". Now that's a very simple idea but it's exactly what Berkshire's trying to do.

There are a lot of people who make a lot of money and everybody hates them and they don't admire they earned the money. I'm not particularly admirable at making money running gambling casinos and we don't own any. We've turned down businesses including a big tobacco business. I don't think Berkshire would work as well if were just terribly shrewd but didn't have a little bit of what the preacher said about my grandfather. We want to have people think of us as having won fairly and used wisely. It works.

WARREN BUFFETT: We were very, very lucky to be born when we were and where we were. You could have dropped us at some other place and time or some other part of the world and things would have turned out differently.

CHARLIE MUNGER: Think of how lucky you were to have your Uncle Fred. Warren had an uncle who was one of the finest men I ever knew. I used to work for him too. A lot of people have terrible relatives.

WARREN BUFFETT: That's another important point. Just yesterday we had a meeting of all my cousins and a whole bunch that we just get together at annual meeting time. There are probably 40 or 50 of us there and they were pulling out some old pictures. Before I answered they were all in these pictures and every one of them, you were so lucky if you had one like that and I had four. I mean they just were… in every way they reinforced a lot of things that needed some reinforcement in my case.

CHARLIE MUNGER: I wish you'd had a couple more. We'd be doing even better.

WARREN BUFFETT: You mentioned my Uncle Fred but my Aunt Katie worked in the store too, my Aunt Alice worked in the store, and you just couldn't have been around better people. I think Charlie would agree with that.

CHARLIE MUNGER: Yes, we were very lucky.

WARREN BUFFETT: Yes, my grandfather was a little tough, however. Tell me what my grandfather used to do when he paid you on Saturday, Charlie.

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well that was very interesting. Warren's a Democrat but he came from different antecedents. I worked for his grandfather, Ernest and he was earnest and when they passed social security which he disapproved of because he thought it reduced self-reliance and he paid me $2 for ten hours work. There was no minimum wage in those days on Saturday and it was a hard ten hours. At the end of the ten hours I came in and he made me give him two pennies which was my contribution to the social security and he gave me two one Dollar bills and a long lecture about the evils of Democrats and the welfare state and the lack of self-reliance and it went on and on and on, so I had the right antecedents too – I had Ernest Buffett telling me what to do.

WARREN BUFFETT: Okay, enough family history.

CHARLIE MUNGER: I haven't overstated that have I, Warren?

WARREN BUFFETT: You haven't overstated it at all.

CHARLIE MUNGER: No, you can't believe it people – and he thought he was doing his duty by the world to do that.

WARREN BUFFETT: Although, we were lucky then. The people we were around when we were young, we were very lucky.

You're famous for making a deal over a day or two with nothing more than a handshake. Other successful acquisitive companies use teams of internal people, outside bankers, consultants and lawyers to do due diligence, often over many months to assess deals. You've done some amazing deals but if you're ever gone, how would you recommend Berkshire change its approach deal making?

WARREN BUFFETT: Yes, I get that question fairly often,.. often from lawyers. In fact, we talked to Munger Tolles, the law firm, and that was one of the questions I got – why we didn't do more due diligence which we would have paid them by the hour for. We've made plenty of mistakes in acquisitions and we've made mistakes in not making acquisitions, but the mistakes are always about making an improper assessment of the economic conditions in the future of the industry or the company. They're not a bad lease; they're not a specific labour contract; they're not a questionable patent; and they're not the things on the checklist for every acquisition by every major corporation in America. Those are not the things that count.

What counts is whether you're wrong about whether you really have to fix on the basic economics and how the industry is likely to develop or whether Amazon's likely to kill them in a few years or that sort of thing. We have not found any due diligence list that gets at what we think are the real risks when we buy a business. We've certainly made at least a half a dozen mistakes and probably a lot more if you get into mistakes of omission, but none of those would have been cured by a lot more due diligence.

They might have been cured by us being a little smarter. It just isn't the things around the checklist that count. Assessing whether a manager who I'm going to hand the $1bn to for his business and he is going to hand me a stock certificate, assessing whether he's going to behave differently in the future in running that business than it has in the past when he owned it. That's incredibly important but there's not a checklist in the world that's going to answer that.