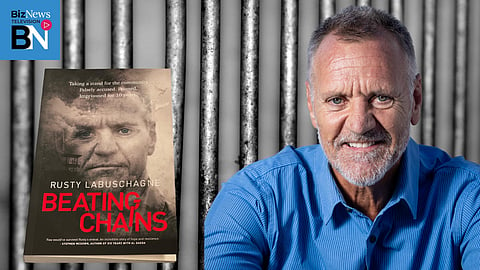

10 years in a Zimbabwean prison – Rusty Labuschagne’s lessons in survival, now told in a book and upcoming film

From representing Zimbabwe in rugby to flying high as a successful safari operator, Rusty Labuschagne’s life came crashing down when he was wrongfully convicted of murdering a poacher in December 2000. In this interview with BizNews, he shares his harrowing journey through a decade in Zimbabwean prisons, where he was crammed into a cell holding 79 men, each allotted barely 33 centimetres of sleeping space. He recounts the unimaginable conditions, watching thousands of inmates die from starvation, disease, and cholera outbreaks while he survived. Rusty relives the cruelty, the loss, and the unexpected clarity that emerged from the darkness, and the lessons he drew about hope, forgiveness, and gratitude. Today he shares those lessons with audiences worldwide, and his memoir, Beating Chains, is now being adapted for film.

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

Support South Africa’s bastion of independent journalism, offering balanced insights on investments, business, and the political economy, by joining BizNews Premium. Register here.

If you prefer WhatsApp for updates, sign up to the BizNews channel here.

Watch here

Listen here

Edited transcript of the interview

Linda van Tilburg (00:01.677)

Rusty Labuschagne was a successful safari operator in Zimbabwe, but his life collapsed in a single moment when he was unjustly convicted of murder in December 2000. He was sentenced to 15 years in a Zimbabwean prison and moved through some of the country’s toughest facilities. After 10 years behind bars, he was finally released. His new book, Beating the Chains, tells the story of what he endured and how he rebuilt his life. And I’m so happy to have Rusty with me in the studio today. Hi Rusty, thanks for joining us. We have to ask you — how did you survive that decade?

Rusty Labuschagne (00:47.807)

Yeah, Linda, maybe I should start by telling you what I went through and where I come from. Would that be okay?

Linda van Tilburg (00:55.565)

Yes, of course.

Rusty Labuschagne (00:56.971)

I’m a fourth generation Zimbabwean from a cattleranching background. I lost my dad at 12, went to boarding school from the age of six, so life was tough. Very humble beginnings. I was crazy about rugby and eventually played several tests for Zimbabwe. But I was always a bushman — I grew up on farms — so I went into the safari business. After a while I realised I could make as much money as the guys I was working for, so I started my own business.

Rusty Labuschagne (01:40.000)

By the year 2000, life was fantastic. I was flying my own aeroplane, had five safari concessions, a fishing resort on Lake Kariba, flashy cars, houseboats, and a big property in Bulawayo. Life was wonderful.

Rusty Labuschagne (01:55.000)

Then the land invasions started. They created chaos and a sense of entitlement, and there was conflict between my fishing resort and a nearby cooperative that kept netting illegally in my area. As a safari operator — whether fishing, guiding, or hunting — you’re responsible for antipoaching. I was always cutting their nets and apprehending them, so tensions were high.

Rusty Labuschagne (02:20.000)

One evening I was out fishing with friends and saw two poachers I knew — notorious guys. I drove my boat towards them with a friend. It was about 5.30pm. If I’d arrested them, it would have been a twohour trip to the authorities and two hours back, so I just wanted to scare them off. I turned the boat, the wake tilted their boat, and they jumped into the water — about one and a half metres deep, three metres from shore. They scrambled out and ran into the bush. We thought nothing more of it.

Rusty Labuschagne (02:55.000)

The next day the police arrived with one of them and accused us of drowning the other.

Rusty Labuschagne (03:05.000)

To cut a long story short, I was framed by the poacher, the police, and the courts in an ugly, politically influenced conspiracy. It went right up to presidential level. A judge tried to help me — he was thrown in prison, not impeached. It was a freefall time in Zimbabwe.

Rusty Labuschagne (03:30.000)

On 3 April 2003, I was convicted of drowning that poacher. No one drowned. There was no body, no evidence, and much of the police evidence was actually in my favour. But it had become political. There was a war between the judge and the president, and unless I was found guilty, they couldn’t prosecute the judge.

Rusty Labuschagne (03:55.000)

Before the judgment, a very powerful political figure phoned me and said, “Russ, you’re going to prison. Get out.” But your reputation — you work your whole life for it, and you can lose it in a second. I could have run, but I would have left my family, my friends, everything I’d built. I would have been running, guilty, and never able to return. I still have my reputation today. If it happened again, I wouldn’t run. People have lost the value of their word.

Rusty Labuschagne (04:35.000)

The conditions were unimaginable. I got 15 years and had to serve 10 — five were removed as remission. The cells were 13 metres long and three metres wide, and we were 79 men. Everyone got 33 centimetres marked on the wall in chalk. That was your space.

Rusty Labuschagne (04:55.000)

For the first eight years, only one set of clothing was allowed: a white shortsleeved shirt and khaki shorts. Underwear was forbidden. After six months you might get a change of clothing — sometimes after nine months — leaving us walking around in tatters. For cushioning on the cold concrete floor, you folded two paperthin, liceridden blankets to fit your 33 centimetres. Your clothes were wrapped around your toothbrush and toothpaste — otherwise they’d be stolen — and that was your pillow. The lice were unimaginable. They bit you day and night, leaving weeping, itchy blisters.

Rusty Labuschagne (05:40.000)

In 2005, I was transferred to Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison. That same year, Harare ran out of water. For three years, 2,200 prisoners were allocated one plastic cup of water a day — dirty orange runoff water from a nearby dam, carried in by farm prisoners. That was for drinking, brushing your teeth, washing your face, bathing — everything — for three years.

Rusty Labuschagne (06:10.000)

In my first six years, I watched over 2,200 men die. Primarily from malnutrition and disease. It was during the cholera outbreak and the Zimdollar crash. There was no food outside the prison, never mind inside.

Rusty Labuschagne (06:30.000)

I was later transferred to Harare Central, a mediumsecurity prison with 1,200 inmates. In eight months during the cholera outbreak, 432 men died — more than a third of us. In one weekend, 22 died.

Rusty Labuschagne (06:55.000)

Linda, I’ll stop with the horrors because they could go on. It was unbelievable. I went from flying high, thinking I was bulletproof, to losing everything and being pushed so low that you have to dig deep to survive. But you grow. You learn lessons others never have to. I found a part of myself I never knew.

Rusty Labuschagne (07:20.000)

People say I have a smiling face for someone who went through all that. But the life lessons I learned… Before prison, it was all about me — my empire, money, more and more. I had no purpose. Now I’m a motivational speaker, speaking all over the world. It’s not about me anymore. It’s about helping others and making a difference. I now have a purpose.

Rusty Labuschagne (07:45.000)

I also found the Lord in prison — I’ll touch on that later — but I can now see how He drew me away from the safari life I loved to find my purpose. He took me from humble beginnings to great success, mixing with the world’s elite, flying in private jets, then put me through that nightmare and stripped everything away — but He prepared me for this calling.

Rusty Labuschagne (08:10.000)

Believe it or not, Linda, I thank God for my 10 years in prison. I’m a better person now than I would ever have been. I’m stronger, I know God better, I understand people more, and I believe it’s made me able to reach out and tell people they can recover from anything life throws at them.

Rusty Labuschagne (08:35.000)

Let me put it this way: do you think anyone can fully recover from a terrible setback like that? You’re looking at someone who did. Living proof that you can recover from whatever life throws at you. No matter what hardships you’re going through, remember — you’re being prepared for where you’re going. God has a plan for each of us.

Rusty Labuschagne (09:00.000)

One of the biggest lessons I learned was forgiveness. I was full of anger, hatred, and bitterness. I had plans for every person involved in my conviction. I knew all the figures. And then one day, after about a year, walking in the exercise yard, I realised I was tired of the anger and bitterness draining me every day.

Rusty Labuschagne (09:25.000)

I looked up and said, “Lord, take care of it. What goes around comes around. They’ll get what they deserve.” I wasn’t a Christian then, but the weight lifted immediately — a feeling of release, like it wasn’t mine to carry anymore. It was as if I’d been keeping a secret for years and suddenly let it go.

Rusty Labuschagne (09:50.000)

People must realise that forgiveness doesn’t change the person who hurt you — it changes you. You can forgive, forget, and move forward, or you can retain, remember, and regret. The choice is yours. But if you say, “I’ll forgive, but I’ll never forget,” then you’re still holding on. I don’t mean forget the lessons — just don’t revisit the pain. You can’t bounce back unless you forgive. Only when you let go of the past can you move forward with your full potential.

Rusty Labuschagne (10:20.000)

Gratitude was huge for me. We all focus on what we don’t have instead of being grateful for what we do. But when you lie in a cell with 78 people and your breath isn’t even your own, gratitude takes on a completely different meaning.

Rusty Labuschagne (10:40.000)

Hope was massive. If I had to choose one word that got me through, it was hope — the anchor of my soul. It helped me see light despite all the darkness. Let your hopes, not your troubles, shape your future. And never look for hope outside yourself. The answers are in you.

Rusty Labuschagne (11:05.000)

If you’d told me in year one that I’d go home in year three, I would have said never. Six weeks, maybe eight, I could cope with — anything beyond that was too painful. Thinking about my fiancée with someone else, or my mates on fishing trips, or our annual marketing trips to Vegas — it was unbearable. So I shut those thoughts out. I counselled myself on how my thoughts affected me physically. Finding happiness in even the smallest things kept me healthy. Those who couldn’t do that died.

Linda van Tilburg (14:39.821)

So this is what you relate in your book. One thing I’ve wondered about — what about trust? How do you regain trust in this journey?

Rusty Labuschagne (14:51.465)

Trust is huge, Linda. Most of us from my era — I’m 65 this year — grew up with rejection issues and fear of failure. That builds unforgiveness. You don’t trust anyone because when someone lets you down, you feel like you’ve failed too. You don’t step out bravely, whether in business or even praying for someone, because you’re scared it won’t work and you’ll fail again. We all carry that. We don’t walk with the confidence we should.

Rusty Labuschagne (15:20.000)

So trust was massive for me. I don’t trust the system anymore. And when you go to prison as an innocent man, a lot goes through your head. I always told my kids everything happens for a reason — now I had to walk my talk, which was very tough in there. But I see it clearly now. I’ve been prepared for what I’m doing, and I’m making a difference in thousands of lives.

Linda van Tilburg (16:31.588)

And you’re also teaching the lessons you learned from prisoners to business leaders now.

Rusty Labuschagne (16:37.271)

Yes — leadership lessons, sales, personal development. I speak at a lot of sales conferences. If you’re not whole, if people don’t see you as someone who’s 100% together, you won’t sell much. People need to look up to you to buy your product. And unless you’re whole — no unforgiveness, fully grateful, walking in confidence — you can’t lead or sell effectively.

Linda van Tilburg (17:12.46)

And this is the journey you’re telling us about in your new book, Beating the Chains.

Rusty Labuschagne (17:18.871)

Yes, Beating the Chains. There’s so much in the book I can’t cover here. The foreword was written by Ian McIntosh, the former Springbok coach. He grew up with my dad in Bulawayo and followed my rugby career, so it was a great honour. The book has sold thousands and I can’t keep up. And we’re in the process of making a movie — it’s going very well. It’ll have a spiritual genre with a conservation twist. I’m very excited.

Linda van Tilburg (18:04.132)

So, are you playing yourself in the movie?

Rusty Labuschagne (18:09.427)

No, we’re looking at Frank Rautenbach — he played Angus Buchan in Faith Like Potatoes. We’re talking to him and he’s keen. There will be three main characters: me, the poacher I once put in prison — who I later found inside with me, ironically — and a very cruel guard. People didn’t know his background, but we did. He was exceptionally cruel. The beatings were unimaginable — it’s all in the book. I watched him kill a man in front of me with a baton to the back of the head.

Rusty Labuschagne (18:55.000)

But that guard had been abducted at 15 during the war, trained to kill, and then dumped into the prison service when the war ended. He was angry, bitter — killing was all he knew. These were the people looking after us. Ninety percent of the wardens were exsoldiers. There was no rehabilitation at all.

Linda van Tilburg (19:49.517)

Sure. Well, Rusty, I’m looking forward to reading your story. It’s amazing how you could still have hope and be so positive — and the lessons you have for all of us. Thank you so much for speaking to us.

Rusty Labuschagne (20:09.943)

It’s a pleasure. The Lord’s been a big part of that, Linda. I got lost during the war in Rhodesia when I was 18. I never grew up religious, never prayed. I was in a dangerous area — because of the war and because of lions and hyena. I was alone, no shirt, no shoes, just a rifle and no hat. Late one evening I got on my knees and prayed for the first time on a mountain. I felt like warm water was being poured over me — a total sense of calm. What happened after that is a long story, but I walked to the road where we lived. It was a desolate place — no roads, no fences, nothing. Wild, in 1979.

Rusty Labuschagne (20:55.000)

I never told anyone what happened on that mountain. Later, in prison, they put me on death row over a cellphone story. I did have a phone, but they couldn’t find it. They put me in a dark cell. Before that, they’d put me in solitary confinement for two years — also over a cellphone story. I did have the phone, but again they couldn’t find it. And even in solitary, I still got another phone — a cheap Nokia — with guards charging it for me.

Rusty Labuschagne (21:30.000)

Then an old girlfriend wrote me a letter saying how nice it was talking to me on the phone. It went through security. They knew I had a phone, searched again, but couldn’t find it. So they put me in what they called the dark cell on death row.

Rusty Labuschagne (21:50.000)

My solitary cell and the deathrow cells were identical: three metres by one metre by three metres, no window, just a vent. In the dark cell, a staircase had been built over the vent, so it was pitch black. The electric light didn’t work either. They used that cell to break people.

Rusty Labuschagne (22:10.000)

They put me in there to force me to reveal the girl’s name. I told them I’d used her phone and couldn’t remember her name. They didn’t believe me. I prayed, I pleaded, but I stuck to it.

Rusty Labuschagne (22:30.000)

On day six, I was allowed out only five minutes in the morning to brush my teeth, five minutes at 10am to shower, and five minutes at 3pm to prepare for lockup. The rest of the time — 23 hours and 45 minutes a day — I was in total darkness. It was like being buried alive. I couldn’t even see my hand.

Rusty Labuschagne (22:55.000)

On day six, I got on my knees and prayed again. I felt the same feeling I’d felt on that mountain. I knew everything would be fine. Thirty minutes later, I faintly heard my Afrikaans mate shouting from the soccer ground, “Hey Russ, everything’s okay, my mate! Don’t worry, everything’s okay!” I jumped up and shouted back. Within ten minutes they unlocked my door and took me to the officer in charge.

Rusty Labuschagne (23:25.000)

His exact words were: “Russ, have you remembered the girl’s name yet?” I said, “No, officer.” He said, “I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I’m going to leave it in God’s hands. You can go back to your cell.”

Rusty Labuschagne (23:45.000)

At that exact moment — while I was praying — my sister was paying him 200 US dollars to get me out of there.

Rusty Labuschagne (24:00.000)

That was a big turning point in my spiritual walk. I had prayed many times in prison and nothing happened, nothing changed. And like I said, I wasn’t a Christian, but I’d had that encounter with the Lord when I got lost. I still didn’t go home for another two and a half years after that deathrow experience, which tested me again. All these things were constantly going through my mind.

Rusty Labuschagne (24:20.000)

When I came out of prison, I’d lost everything. Everyone was ten years ahead. I thought, “If God’s here, how come I’m like this?” But long story short, Linda, many other spiritual experiences followed. Four years ago, I gave my life to the Lord completely.

Linda van Tilburg (24:35.745)

That’s amazing. That’s a good thing.

Rusty Labuschagne (25:01.643)

I stopped drinking. I always enjoyed a good party — being a rugby player and in the safari business — but I could never have imagined the peace and happiness I now experience every day. I don’t have anything like I used to have, but I have peace. And that’s the lesson: you won’t find peace unless you find Jesus.