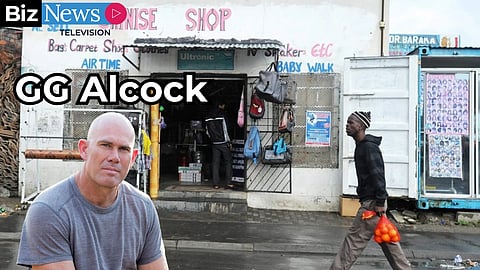

GG Alcock: Ignorance shaped destructive reaction to ‘Spaza poisoned food’ fracas

Informal sector expert GG Alcock is appalled at the ignorance on display from politicians who tried to intervene in the recent poisoned snack food scandal that killed 23 children. He explains how the reaction was driven by a populist political agenda rather than any intention to address the underlying problem. Alcock opens a window to the ugly reality of those living with a preventible infestation of rodents and other pests in this interview with BizNews editor Alec Hogg.

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

The seventh BizNews Conference, BNC#7, is to be held in Hermanus from March 11 to 13, 2025. The 2025 BizNews Conference is designed to provide an excellent opportunity for members of the BizNews community to interact directly with the keynote speakers, old (and new) friends from previous BNC events – and to interact with members of the BizNews team. Register for BNC#7 here.

If you prefer WhatsApp for updates, sign up to the BizNews channel here

Watch here

Listen here

BizNews Reporter

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

The spaza shop sector, a critical part of South Africa's informal economy, is under scrutiny following a series of tragedies and government interventions. GG Alcock, an expert in informal economics, sheds light on the challenges and misconceptions surrounding this vibrant yet fragile sector in a recent conversation with BizNews founder Alec Hogg.

A tragic catalyst: Poisoning and pesticides

Towards the end of 2024, South Africa was shaken by reports of children dying after consuming poisoned food allegedly sourced from spaza shops. Initial narratives blamed outdated food sold in these outlets. However, Alcock refuted these claims early, and investigations later revealed the primary cause: contamination from pesticides used in homes and shops. These pesticides, freely sold in informal markets, were a desperate measure against rampant rat infestations, a problem exacerbated by municipal failures to manage waste in townships.

Rubbish heaps in areas like Alexandra and Khayelitsha have become breeding grounds for pests, leading residents to resort to hazardous chemicals. Alcock points out that this tragedy stems from systemic issues, including poor waste management and inadequate regulation of dangerous pesticides.

Political opportunism and misplaced blame

The poisoning incidents provided fertile ground for political posturing, with foreign-owned spaza shops becoming scapegoats. Alcock criticized the narrative that ousting Somali and Ethiopian traders would create opportunities for South Africans, calling it a "waste of a tragedy." Instead of addressing the root causes, the government focused on demonizing foreign shop owners, imposing rushed regulations that disrupted the sector.

Alcock highlighted the disconnect between policymakers and the realities of the informal sector. "They have this image of a dark, rat-infested spaza shop run by unwashed foreigners," he said, contrasting it with the sophisticated operations he has observed, complete with barcoding systems and well-stocked shelves.

Economic impacts and resilience

The government's actions caused significant initial disruptions. Spaza shops halted restocking, fearing closure, and wholesalers faced empty aisles. Yet, the sector's resilience shone through. By December, spaza shops were rebounding, aided by Mozambican immigrants who stayed in South Africa for the holidays, increasing demand.

Despite the chaos, Alcock noted the informal economy's adaptability. Foreign traders partnered with South African landlords to navigate new registration requirements, often greased by municipal bribes. "These traders have survived crocodile-infested rivers to get here. It'll take more than bureaucracy to send them back," Alcock quipped.

The role of Big Business and misplaced priorities

Alcock dismissed the notion of corporate lobbying against spaza shops, emphasizing instead their symbiotic relationship. Companies like Shoprite supply spaza shops through wholesale divisions, recognizing their value in reaching underserved communities. However, the broader informal economy remains misunderstood and undervalued by the government.

The focus on spaza shops also overshadows the sector's broader economic contributions. Alcock estimated it generates R187 billion annually and provides essential goods and services in areas where formal retail struggles to operate. Yet, government actions often undermine these benefits, prioritizing populist narratives over pragmatic solutions.

Lessons for 2025 and beyond

Alcock believes the solution lies in embracing the strengths of the informal sector rather than stifling it with ill-conceived regulations. He advocates for collaboration between government and businesses that understand the ground realities. "Business is the solution to most of our issues," he asserted, citing examples like Capitec and Shoprite, which have successfully engaged with informal markets.

South Africa's spaza shop saga underscores the importance of nuanced policymaking informed by on-the-ground realities. As the informal sector rebounds from yet another crisis, its resilience offers a lesson in the power of community-driven solutions, even amid systemic failures. For policymakers, the message is clear: to support the economy's backbone, they must step out of their offices and into the bustling streets of the townships.

Read also: