Investor Insights

Why this round of inflation data matters a great deal: John Authers

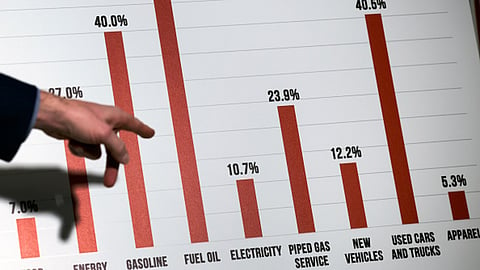

This week's focus rests squarely on US inflation.

In a whirlwind of economic data and monetary policy shifts, this week's focus rests squarely on US inflation, a metric with profound implications for markets and consumers alike. As central banks contemplate rate cuts amidst mixed economic signals, the legacy of investing luminary Jim Simons leaves an indelible mark, his groundbreaking strategies defying conventional wisdom. As we navigate this landscape of uncertainty, understanding the past may illuminate the path forward.

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

By John Authers

Today's Points:

- Yes, this week's US inflation numbers matter — a lot.

- Politics do affect consumer confidence, but the message from Michigan is valid.

- Central banks are in a mood to cut rates — and Sweden's Riksbank did.

- AND Rest in Peace, Renaissance Man Jim Simons.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___