Leadership

The Economist: South Africa’s foreign minister (next president?) wants better relations with the West

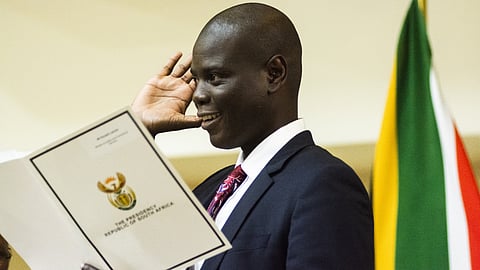

Ronald Lamola’s view counts: he may be the next president

From The Economist, published under licence. The original article can be found on www.economist.com

© 2024 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved.

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

Join us for BizNews' first investment-focused conference on Thursday, 12 September, in Hermanus, featuring top experts like Frans Cronje, Piet Viljoen, and more. Get insights on electricity and exploiting SA's gas bounty from new and familiar faces. Register here.

The Economist

Ronald Lamola's view counts: he may be the next president

___STEADY_PAYWALL___