Ted Black: Lessons in crisis management from the Covid pandemic

In a world where the WHO claims the Covid pandemic is over but advises against complacency, a UK enquiry seeks to evaluate the country's preparedness, measures taken, and lessons learned. With a team of over 150 lawyers, the enquiry aims to surpass its £114 million budget. Meanwhile, the Institute for Economic Affairs challenges the effectiveness of lockdowns, suggesting the use of control charts for better decision-making. Ted Black delves into the importance of understanding variation and root causes in managing crises. He also highlights the need for results-driven projects led by frontline workers to improve systems, citing a successful example in a hospital setting.

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

It's Easier to Wreck a System than Improve It

By Ted Black

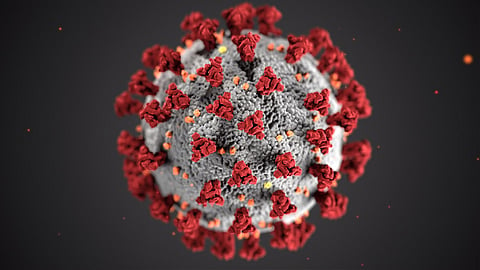

WHO says the Covid global pandemic is over but warns us not to drop our guard, dismantle systems built, or think Covid-19 is over. To that end, UK's no time limit enquiry wants to find out: How prepared the country was? Were measures strict enough? What lessons are there?

Using more than 150 lawyers, it's bound to beat its planned cost of ₤114 million by far. It'll be time and yet more money wasted if its focus is more on the past than the present and future.

Meanwhile, UK's Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA) has already concluded lockdowns made little impact on the spread of the virus. Using one of Dr. Walter Shewhart's simple, brilliant 3-Sigma "control charts" would've told them that this time three years ago. Few managers use them.

Much more than a tool to improve product quality, it helps us understand random variation and how it affects all of us. Using it goes deep into how we learn, know and cope with life. Our minds tell us that for every problem or challenge we face, there are always causes – seen or assumed for anything that concerns us.

It's this knowledge that makes us act. We push buttons and pull levers – set "stretch" targets, use carrots and sticks – that we think will make happen what we want to happen. They are our theories of the way the world works. We use them all the time. But do they work well, or often misdirect us?

Below is a control chart showing England & Wales total death rate every four weeks from 2015 to year-to-date. Governments worldwide harnessed our fear of it to force blind obedience to the arbitrary rules they set.

Countless, mostly unknown factors cause variation within any "system" you measure. Using three standard deviations above and below the average based on the five years before Covid (CL – Central Line), the data points for the most part fall within "Upper" and "Lower Natural Process Limits" (LNPL) of the "system".

They vary because of "Common Causes" within it and, as you can see, are predictable. The red points show unusual shocks or "Special Causes" you must investigate. However, there's another one within the limits. Starting late 2021, there's a pattern change — nine consecutive data points (circled) above the average (CL – Central Line) – which also signals a "Special Cause" to explore.

In a way, even the deaths above the upper limit are predictable – they come in winter's cold weather and from the sickness it brings. The trouble comes when we treat all causes as "Special". Most of us do, and our knee jerk reactions cause more variation, wasted effort, and costs.

As to the pattern change, of the last 23 data points since it started only one is below the average, and very slightly at that.

The next chart shows the death rate at a new level.

The average 4-weekly rate of 45 900 since end 2021 is 12% higher and only 300 less than in 2020 – the worst year of the pandemic. The natural upper limit is now 56 000 and January's 62 305 breached it with Covid at only 3,5% of all deaths – now less than 2%.

Delve a bit deeper into the data and you find the universal 20/80 Law applies. Less than 20% of the population (>65 years) account for around 85% of all deaths and more than 90% of all Covid ones. The virus culled the sick, elderly and old, but killed fewer than 2% of those below fifty. As for "excess deaths" – those above the upper limit of 46 700 – there were 82 000 in 2020/21, and so far in 2023 the number is 20 000.

Isn't this where enquiries should focus and ask: "What are the root causes of today's numbers and the best, next steps and measures to counter the rising trend?"

In the short term we can safely predict deaths will fall until late summer but then what … is this definitely a new level?

If it is, then doesn't the knee jerk reaction to the pandemic confirm yet again how much easier it is to damage and wreck systems than improve their productivity? Authoritarian governments, especially socialist ones, are perfect exemplars of doing just that.

So what's the answer?

Go to operating people who make systems work day-to-day. Have them design results-driven projects to improve it. Drop things like "diversity training", studies, surveys or some other useless activity head office bureaucrats impose.

An inspiring example in a hospital system is a recent one at Groote Schuur, Cape Town. It's written up by Elri Voigt in Spotlight and describes how a small team of health workers designed and ran a project called "Surgery Recovery". It slashed a backlog of 1500 elective surgeries two months ahead of plan and team members grew and developed in the process.

"Releasing" people to do what they did is a great example of effective management in action.

Read also: