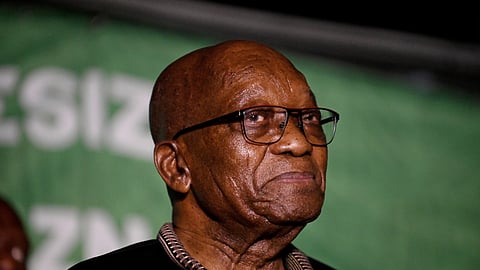

RW Johnson: “Foolish old man” Jacob Zuma and the MKP disaster

In a tale echoing Shirley Williams' political missteps, Jacob Zuma's re-emergence mirrors her downfall. From ANC prominence to leading the MKP, Zuma's impulsive decisions and lack of structure have led to chaos. His hasty purges and erratic manifesto blend Marxism with Zulu feudalism, baffling voters. Rejected by the GNU and KZN government, the MKP's disarray disappoints supporters expecting patronage. Zuma's legacy risks a farcical end, echoing Williams' journey from promise to political irrelevance.

Sign up for your early morning brew of the BizNews Insider to keep you up to speed with the content that matters. The newsletter will land in your inbox at 5:30am weekdays. Register here.

Join us for BizNews' first investment-focused conference on Thursday, 12 September, in Hermanus, featuring top experts like Frans Cronje, Piet Viljoen, and more. Get insights on electricity and exploiting SA's gas bounty from new and familiar faces. Register here.

By R.W. Johnson

___STEADY_PAYWALL___