Widening budget gap threatens SA’s last standing credit rating as Eskom bailouts drain fiscus

By Prinesha Naidoo

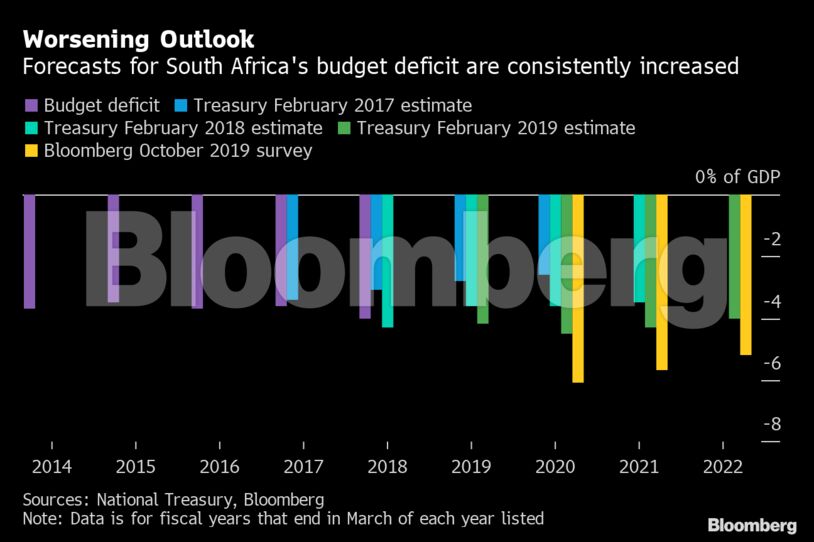

(Bloomberg) – Billions of dollars in bailouts for South Africa's power utility will probably widen the budget deficit to the biggest since the financial crisis, threatening the nation's remaining investment-grade credit rating.

Power shortages and policy uncertainty have damped economic growth and plunged business confidence to multi-decade lows, while the revenue service has struggled to meet tax estimates. Finance Minister Tito Mboweni reiterated in July that the bailouts will come at a cost to taxpayers, who have faced a series of tax hikes since 2015, including the first increase in VAT since 1993.

"We cannot rely on fiscal policy to stimulate the economy," Lullu Krugel, the chief economist at PwC, said by phone from Johannesburg. "If we see a global economic downturn, we don't have any buffer against it. There's no chance of spending ourselves out of it like we did in 2008 and 2009."

South Africa's R128bn ($8.7bn) three-year package for power producer Eskom – the utility that's seen as the biggest risk to the economy – will add to state liabilities and widen the deficit, Moody's Investors Service said last month. It's the only major ratings company that still assesses the country's debt at investment grade.

The utility has R450bn of outstanding debt.

"The sheer scale of Eskom's debt is daunting," President Cyril Ramaphosa said on Monday in a weekly letter to the nation. "Further bailouts are putting pressure on an already constrained fiscus," he said adding that support for the power company is dependent on "stringent conditions".

Junk risk

Analysts are speculating that Moody's may cut the stable outlook on the Baa3 rating to negative because of rising debt and lower economic-growth projections, putting the country on the verge of another junk rating.

A downgrade would leave South Africa without an investment-grade ranking for the first time in 25 years, and see the nation fall out of key debt gauges including the FTSE World Government Bond Index, prompting capital outflows.

Mboweni's policy statement needs to "send a signal to rating agencies that the state remains committed to fiscal consolidation," said Jeffrey Schultz, a senior economist at BNP Paribas South Africa. The economy needs non-interest spending cuts of more than 2% of GDP to stabilise debt metrics "today" although a 0.5% reduction within a solid macroeconomic plan would make for a credible budget, he said.

Weak growth

The National Treasury has asked government departments to propose how to reduce expenditure in a way that has the least impact on service delivery. It sought cuts of 5% for 2020-21, and 6% and 7% for the next two years. That could be as much as R300bn over three years.

Failure to narrow the budget gap could raise debt, including guarantees to Eskom, to more than 70% of gross domestic product in the medium term, said Moody's. Fitch Ratings sees state debt increasing to 68% of GDP by 2021-22 from about 56% now, it said in July.

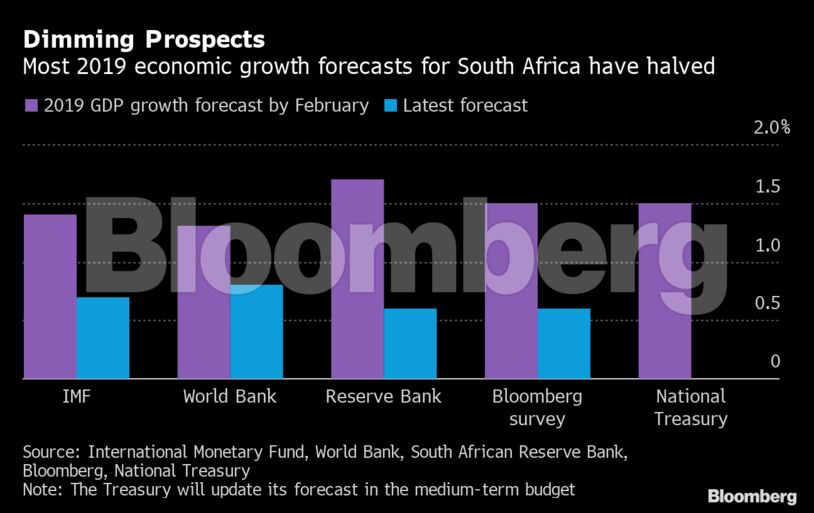

Weak economic growth remains a major constraint to the fiscal outlook. A Bloomberg survey of 28 economists sees GDP expanding 0.6% this year, in line with the central bank's forecasts. That would be the lowest annual rate since 2016.

"Next year, if the global economy doesn't hit the brakes too severely, we could get up to 1.5% or thereabout – but the bottom line is if we keep on in this region of 1%-1.5%, it's not enough, it's not going to work," PwC's Krugel said. "We need some serious structural changes."