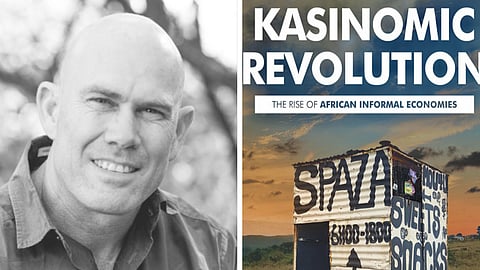

GG Alcock – On ‘Kasipolitans’; a landgrab in booming township economy; and why Stalinist ANC on wrong page with its ‘500 black industrialists’

By forcing people to stay at home, Covid-19 lockdowns accelerated the development of township businesses to the point where many residents now support them and simply refuse to return to pre-pandemic shopping habits. In this fascinating interview, entrepreneur, author and informal economy specialist GG Alcock explains how South African retailers are waking up to this reality, and have launched a land grab into communities inhabited by 'Kasipolitans.' Alcock also rips into the ANC's waste of taxpayer funds to subsidise its '500 black industrialists', a group of cadres who qualify for 'Stalinist' style taxpayer handouts through their connections rather than business acumen. Taxpayers would be far better served, he reckons, were SA's government to acknowledge already successful township entrepreneurs who have succeeded by overcoming daunting odds – and whose businesses would rocket with even a modicum of financial support. – Alec Hogg

GG Alcock on the boom of the informal kasi economy

Business in the sector is booming. It's doing really well for a number of reasons which has actually prompted a lot of companies, retailers and so on to enter into that space. And the question is, why is it booming? To a large extent, what has happened is things like cost of transport, and lockdowns have in essence created a situation where people are shopping locally. I talk a lot about 'kasipolitans,' people who are very rooted in the township for everything, from entertainment to shopping. Staying at home because of Covid meant that people started looking around themselves in terms of where they go shopping and to get their hair done and so on. It kind of coincided with things like the cost of fuel and the inconvenience and cost of taxis. If you go to the shopping centre, the queues since Covid are insane in the townships, people are standing in queues for 40 minutes to 2 hours.

On using the term kasi and what it refers to

When we look at the informal economy, we almost have to separate the informal economy and the township economy. And within the township economy, it's increasingly difficult to define what a township is. You've got the historical townships, and if you look at Soweto as an example, there were 29 suburbs in Soweto, now there are 35 suburbs and those new suburbs look prettier, like they're not really a township, they are townhouses and clusters. And then, of course, many of the townships have kind of spread into surrounding areas, places like Naturena and so on. Wherever the townships are neighbouring old white suburbs, they have become very much kasi-fied. You'll find a car wash and a shisa nyama.

On how the formal economy and media are ignoring the reality of what is happening in the informal economy

My second business book was called KasiNomic Revolution because I said there's a revolution happening in informal economies throughout Africa. The scale of those economies is untapped and really unrealised. And equally, these figures around unemployment are absolute rubbish because no one's considering the businesses, and other forms of income that are actually being earned in those kinds of spaces.

In 2019 I found something that was closer to 12% and I'd stick to the same number now. Just to dwell on the unemployment figures, I've said around 12% real unemployment and if you want to take the figures of say 40% that are touted around, you've got to place the word 'formal' unemployment in front of that word because that reflects to people who earn a paycheck, they have a pay slip and earn a salary or a wage. If you look outside of that, if you look at this massive informal economy, the spaza sector's 150 billion rand sector, fast food is a 90 billion rand a year sector. The taxi industry is a 50 billion rand a year sector. Traditional herbal medicines, 18 billion rand sector. Hair salons, a 10 billion rand sector. None of them have payslips.

Then over and above that, there's a lot of passive income that we don't measure. So, for instance, all the spazas are primarily foreigners or immigrant traders. They pay 25 billion rand a year in rental to South African owners of the houses that their spaza is on. There's another 20 billion rand a year in the backroom rental sector, which is a booming sector.

GG on the growth of the informal economy

So my question to people is often, is it true that townships have large households with six or eight people per household? Well, Stats SA shows 25.7% of households are one person households and 50% of households are under three people per household. So 70 odd percent of households in South Africa are either 1 or under three people per household.

Don't be swayed by anecdotal or media bias, which tells you a story of a granny who lives with eight grandchildren and absolute poverty in a shack, and then extrapolate that to say it's representative of the total population. Yes, those stories are true. Yes, there are unemployed people. Yes, there are poor people who live in shacks but 86% of households in South Africa live in formal dwellings. So informal dwellings represent a tiny minority. And why is that important? That's important because when you look at it increasingly, if you're in a small household, you start spending more money on yourself and you start buying smaller pick sizes.

I've heard retailers say that consumers are under pressure because they're buying smaller pack sizes; are they buying smaller pick sizes because their budgets are under pressure, or because they're actually one or three people households? So one person doesn't need 12kg of flour or rice, they need 2kg. People are spending more on comfort, if you live in a formal house, you start spending on things like a couch and a flat screen TV.

We see this in the building and furnishing industry in the townships, it's just really booming, and we also see it in hair care and nails. The hair salon sector is booming as are the suppliers for those companies. If we look at the fast food sector, that's booming. Why is it booming? Because again, if you're a small household, why would you go and cook?

The wholesale sector is booming. Let's look at the retailers. Shoprite is investing heavily in Usave and Usave Ekasi. Usave is in essence a local neighbourhood shop, Usave Ekasi is a container based offering, that's basically got a mini Usave in it. There are about 280 Usaves across the country, which is their smaller version of Shoprite. And Pick n Pay has just announced that they're going to launch a Pick n Pay Red format.

Mr. Price bought out Power Fashion. Most people had never heard of Power Fashion, an affordable fashion business in townships or in informal kinds of environments, and they bought Studio 88. I think they paid 3 billion rand for it.

On the key insights from the kasi economy

A brilliant insight is an understanding of the fact that consumers in the kasi sector, the township economy, are doing better, and have more money than the dramatic headlines tell you.

The second part about it is this recognition of local purchases happening in what I call township high streets. If you look at the main arterials in the townships, increasingly businesses aggregating around that, that's where the footfalls are. That's where consumers are shopping. It's about the growth of the local neighbourhood, the smaller households. Covid has accelerated that growth dramatically in the township space.

There are 530 historical townships in South Africa. I built a database of the 80 that I call townships and township clusters. If you look to the north of Pretoria, there's a township called Soshanguve and next door to it is Mabopane, Garankuwe and Winterveld, that's what I call a township cluster. It's one geographic space and one economic ecosystem. Now, if you look at those clusters, they represent 80% of our urban turnovers, and economic activity. If you're not in those spaces, you're kind of out.

Read also: