Could opposition parties with ‘boggerol’ in common rule SA? – Chuck Stephens

LONDON — As tired of everybody in the UK is of the Brexit debate, one newscaster last night quoted a Cabinet minister saying, "F***k knows, I am past caring, it's like the living dead in here" – it does offer a good indication of how difficult it is to get political parties from across the spectrum to agree. How does 7 amendments to UK Prime Minister Theresa May's Brexit deal all voted down by Westminster sound to you? The only thing they agree on, is that they don't agree. And 29 March was supposed to be Brexit Day. It gives us a good indication of how difficult it is to get parties who literally have boggerol in common to work to a common goal; the Democratic Alliance and the Economic Freedom Fighters are another example of this. They battled on municipal front, where the issues are water and electricity, can you imagine what it would be like when it is about bigger issues? Julius Malema weighing in on foreign policy? Eish. But if the ANC does in fact lose the majority in Parliament, that may become a reality. Chuck Stephens from the Desmond Tutu Centre says coalition is possible with tolerable compromises. He does not quite share my cynicism about politicians and says it could offer exciting prospects if the ANC sinks below 50%. My experience is they only work together and compromise if they are backed into a corner and have no other choice. But this time there may be a bigger prize and Chuck's scenarios could become interesting. The big prize of wresting power out of the hands of the ANC could put very strange bedfellows together. – Linda van Tilburg

By Chuck Stephens*

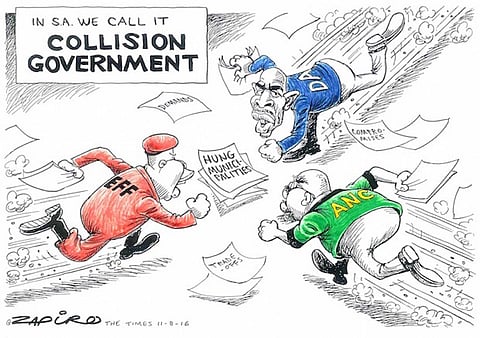

Since the 2016 municipal elections in South Africa, the reality of coalition government has become apparent. It works, but it is relatively unstable and fraught with inconvenience.

In fact, a distinction can be made between minority governments and coalitions. Minority governments are like Theresa May – dependent on another party to get a majority vote. But the party with more votes than anyone else, albeit less than 50%, runs the government. Whereas coalitions are like they have in Germany – a number of parties forming a conglomerate, that forms the government.

This moves far away from the dominant model in South Africa – the "vanguard party" which is a genetic throwback to One-Party States. The 2019 elections could well be the end of that era, but much depends on whether voters can start to believe that a coalition can really function effectively.

The mother-of-all-parliaments in the UK is finding it hard to pass its Brexit deal, because it has two oppositions – one that want the UK to remain in the EU, and the other that wants a "hard Brexit". These are called the Remainers and the Leavers, while the Prime Minister is trying to get a "via media" past the post. The difficulties of doing this without a 50% majority have highlighted in this "shambles". But it has brought to light the need for new processes.

Enter the "indicative vote" by which parliament can seek any prospect of convergence on one person or party's motion. In fact, these varied suggestions on both side have also failed to muster a majority. This is what people worry about when they think about the prospect of a DA-led coalition government in South Africa after May 8th.

If the ANC sinks down to let's say 48 per cent of the vote, it could run a "minority government" by borrowing votes from some other parties. Or the other parties could decide that they all want to get rid of the ANC, and glom together their 52%. But in this mix, the DA would only hold about half of the seats. So it would not be in a position to run a "minority government" but rather a coalition.

In South Africa, a joint venture is something like a marriage in-community-of-property. Just as "two become one flesh" in a marriage, so also, a coalition would take on a new life of its own. It would become a "coalition government" and that raises the key question – how it would get decisions past the post of 50%?

One way to do this would be for coalitions members to agree on the use of "ranked-choice voting".

In this kind of voting it is not just the "ayes" versus the "nays". While your first choice matters most, your second and third choice also score some points. For example, if there are five choices and you ask each voter to rank them from 1 to 5, then first choice wins 5 points, second choice 4 points, and so forth. Even your last choice wins a point.

In this kind of voting election results look for convergence of opinion. You can vote several times until you narrow it down to two choices, at which time one vote does get past the post. But the truth is that the decision may be no-one's first choice. That is what is meant by "tolerable compromises".

Using an approach like this would allow many parties each with a few seats to find a way to govern.

This could also include Independents, if they manage to find a way into our elections. There are 400 seats in Parliament. Fifty-two percent of that is 208 seats. If a coalition is formed with 208 seats, it could muster majority votes if and only if all members of the coalition government buy into this method of voting. Otherwise, you could end up with a hung parliament.

After the 2016 municipal election, the EFF remained aloof from coalitions. It said that it would support the coalitions with its votes, to keep the ANC out of power. But it did not want to get into bed with the DA. This is the kind of attitude that has led the mother-of-all-parliaments in the UK into its embarrassing shambles. Some would say that it has brought Democracy into disrepute.

A coalition government would certainly take the power away from the parties and put it into the hands of MPs. For a change. This would align better with the Constitution than vanguardism, which has also brought Democracy into disrepute – here in South Africa. The PR system plays right into the hands of patronage, which open the doors to corruption, letting State Capture in.

Ranked-choice voting could make "coalition government" a workable reality in South Africa. But the opposition parties need to weigh in to this prospect during the election campaign.

Which raises the question – is the EFF just a project? Or is it an organisation? Its focus has been always BEE land reform and that momentum has now been overtaken by the ANC. This leaves the EFF looking a bit out of sorts. So will it shrink from its ten percent market share? Or does it really want to grow and engage with other issues as well? If so, it needs to commit to getting involved in a future "coalition government", not just remaining aloof as a legend in its own mind.

If the ANC sinks under 50%, let's say to 48%, it will need some extra votes, but the proportions are such that the EFF would never be a "partner". Forty-eight percent and ten percent total fifty eight percent. That would make the EFF a 17% partner – it's not much. Whereas in a real "coalition government" the EFF would hold a significant stake and be able to influence decision making within the national assembly in a much more significant way.

Also, the three front-runners – according to both recent polls – only gather 88% of voting pledges. There is a full 12% sitting with the other 42 parties. Those parties will remain insignificant in an ANC "minority government" – but between them, they would hold a quarter of the seats in a coalition government.

If Democracy is a disappointment to voters in South Africa, moving past vanguardism and into "coalition government" actually offers some exciting prospects. It will involve more parties and more younger people, and not just in a nominal way.

- Chuck Stephens, Executive Director of the Desmond Tutu Centre for Leadership.